BAGRAM AIRFIELD, Afghanistan—It’s 3 a.m. and U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. John Cardenas shouldn’t be awake. Though he has set his alarm for 5 a.m., he has begun to wonder why he even bothers anymore, since his beeping pager seems to start his day more often than not. He looks at his pager, noting the degree of injuries and the number of traumas. Knowing his team of airmen will need his leadership, he puts on his uniform, ties his boots, slings his M-16 rifle onto his shoulder, and begins his 12- to-14-hour day along the rocky path leading to Craig Joint Theater Hospital (CJTH), Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan.

This is what a normal day looks like for Cardenas, who is half-way through a six-month deployment from Travis Air Force Base, CA, as a laboratory technician in the 455th Expeditionary Medical Group. The base hosts the busiest airfield in the country, where it’s a central hub for counterterrorism operations; the base is home to cargo aircraft that keep forward operating bases supplied as well as F-16 Viper fighter aircraft that target enemy networks throughout the country.

It’s also the location of the premier Role III combat medical hospital in Afghanistan. Its patients include not only U.S. and Coalition (i.e., NATO) forces, but also Afghan soldiers, U.S. contractors, Afghan government leaders, and occasionally Afghan civilians injured as a direct result of combat operations.

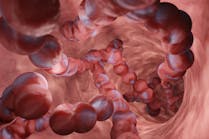

An integral piece of the hospital’s quality of care is the laboratory. This five-member Air Force team is part of the Diagnostics and Therapeutics Flight, consisting of the Laboratory, Pharmacy, Diagnostic Imaging, and Nutritional Medicine departments, and ranging in age from 24 to 49, is responsible for administering approximately sixty thousand diagnostic tests and 1,500 blood product transfusions each year. They also serve twenty forward operating bases, or FOBs, outside of Bagram, which are often located in the mountains with poor infrastructure.

According to Lt. Col. Patrick Kennedy, the Diagnostics and Therapeutics flight commander, 70 percent of all diagnoses in every hospital are based on lab results; however, the CJTH’s laboratory is all the more important in a combat zone where blood product transfusion is essential for stabilizing and sustaining combat casualties.

“The criticality of the CJTH lab is increased based on our top-tier surgical capability in Afghanistan,” Kennedy says. This rings especially true in the event of a mass casualty (MASCAL) situation, during which 100 percent of the hospital staff reports for duty. A MASCAL is defined as when there’s an influx of trauma patients, typically greater than nine, and it varies depending on the degree of injuries seen. If assigned to the trauma bay where the hospital receives patients from a hostile environment, the lab staff will also wear protective eyeglasses in case a patient arrives with explosive material under his or her clothing.

The hospital team then immediately begins the triage process to take care of the most critical injuries first. While this happens, the lab ensures blood is available as needed. Fortunately, the lab is co-located with the blood supply detachment (BSD), which supplies blood to the entire area of operations, including CJTH.

“In the event of a MASCAL, the BSD and lab work in conjunction as consultants for the walking blood bank,” says Kennedy. Though the name sounds quirky, a walking blood bank is a list of prescreened individuals who’ve agreed to donate blood for specific emergencies. “In the States we would contact other blood banks, but in a combat zone we don’t have that luxury.”

Not having certain luxuries that laboratorians might expect in the U.S. doesn’t mean, however, that the lab skimps on quality of care.

“Patient safety and quality assurance go hand-in-hand,” says Staff Sgt. Jefonda Smith, noncommissioned officer-in-charge of Laboratory Services. “Therefore, even with the austere challenges of a combat zone, such as caustic water, difficult supply chains, and instrumentation issues, our goal is still to maintain Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act and College of American Pathologists standards.”

Smith, who is deployed from Joint Base Charleston, SC, says her proudest moment thus far has been seeing the improvements to expedite patient care.

“We were able to install a wireless printer in the trauma bay, which allowed us to communicate lab results with doctors 71 percent faster,” she says.

Ensuring the team is ready to support any medical emergency equates to a 24/7 on-call schedule. They also work at least 12-hour days, with a “low-ops” day mixed in to take care of personal matters. If there’s an especially high number of traumas, lab leadership will implement work-rest cycles, allowing for sustainable support to the hospital.

Yet even a more sustainable schedule can’t always prepare you for what comes through the trauma bay.

“The hardest thing I have had to do was seeing two young civilian casualties,” says Cardenas. According to Cardenas, U.S. Marines and Georgian security forces had rendered life-saving care to two children, who sustained injuries from a Taliban suicide bomb outside of base, and then brought them to CJTH.

“Our warrior medics were able to get them back on their feet quickly. However, during the initial days, the boys would not smile and they were probably scared,” says Cardenas. “So I turned to the sport I love, soccer. I had found out that the boys were playing soccer when they were hurt, so I thought this would be a great way to connect and get them to smile.” It worked. He took the kids outside to show them a couple of tricks.

“It was probably the best part of my deployment so far, when I saw the little one smile for the first time,” says Cardenas. As the patients’ injuries began to improve, they also joined in with the medics to kick the ball around.

Moments like these provide the five-member team a welcome solace from the emotional toll exacted by such rigorous schedules and family separation.

“It has definitely been difficult to be away from my family,” says Cardenas. “I have an awesome wife, Laura, who is taking care of our three kids all by herself. Between soccer games and balancing the everyday schedule, she is exhausted but never complains.”

Yet, CJTH team members never lose sight of the importance of what their work provides to the overall mission in Afghanistan.

“All patients that come through CJTH are patients, regardless of rank, age, gender, nationality, or affiliation,” says Kennedy. “The more people that have a positive experience, the more ambassadors that are created.”

Smith adds to Kennedy’s sentiments: “It’s amazing being part of a team knowing that we are all Americans united under one common goal, which is to save patients.”

Capt. Lyndsey Horn, 455th Air Expeditionary Wing