CMS’ coverage of HbA1c testing for diabetes screening is a good start — But we can do more

In November, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced policy changes for Medicare payments under its Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Included in these changes was an update countless experts believe was a long time coming: the new proposal now includes coverage of hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) testing for diabetes and prediabetes screening.1 Lauded by many, the American Medical Association called the addition “a significant step forward.”2 The change was in response to concerns raised by medical groups, including the Diabetes Advocacy Alliance.

What is HbA1c, and why is it important for diabetes screening?

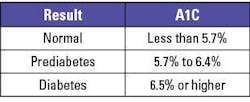

HbA1c testing is a single non-fasting blood test that assesses a patient’s average blood sugar levels over time, and has long been used as a measure of disease management for individuals who have been diagnosed with diabetes. Patients with known diabetes typically have their HbA1c measured twice yearly to assess the level of control of their disease.3 However, beginning in 2010, HbA1c was recognized by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines as an accepted method by which diabetes can be diagnosed and to identify patients with prediabetes.4 Since it can be measured in a single non-fasting specimen, HbA1c is a powerful screening tool to diagnose diabetes – particularly type 2, which often develops in adulthood and affects the majority of (90-95%) America’s 38 million individuals with diabetes.5 Although recognized by the ADA as an accepted means to diagnose diabetes and prediabetes, HbA1c was not recognized or reimbursed for this purpose by CMS until November of 2023.

While a fasting blood sugar test has long been a primary method of screening for diabetes and prediabetes, HbA1c and fasting glucose may give somewhat different answers in specific individuals and the measurement of both provides a better view of an individual’s metabolic state.6 Other studies have demonstrated additional utility in HbA1c testing, such as the ability to predict costly micro- and macro-vascular clinical complications that may manifest in patients down the line, ultimately allowing for earlier interventions and therefore lowering the cost of care over time.7

Though it can be as effective as fasting blood sugar testing, HbA1c testing as a screening measure for diabetes is not a replacement for this test. To provide the most comprehensive look at a patient’s health, and craft an effective treatment plan, a physician should order both tests. CMS’ coverage of HbA1c testing as a screening measure for diabetes and prediabetes is still a step forward — so long as it takes care not to minimize the important role fasting blood sugar testing plays in patient care. Both tests have clinical utility and are vital in getting patients diagnosed and treatment provided as soon as possible.

How diabetes screening evolves disease management

Diabetes is a condition that is manageable with lifestyle changes and, in some cases, reversible. Certain modifications to a person’s diet or exercise regimen can greatly impact their health. But patients cannot manage what they don’t know they have. While approximately 98 million American adults have prediabetes – an elevation of blood sugar levels not yet high enough to be diagnosable as type 2 diabetes – more than 80% of these individuals do not know they have it.8 As prediabetes can put a person at increased risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or stroke, it is important to ensure these individuals are aware of their high blood sugar levels as soon as possible.

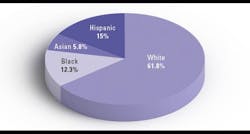

Some of these patients may be unaware because of barriers to care that prevent them from accessing screenings. Research has shown racial and ethnic minority and low-income adult populations consistently remain at a higher risk of type 2 diabetes.9 These populations are also impacted by social determinants of health, like economic instability or lack of insurance coverage, which can make receiving needed care difficult to obtain. In this way, CMS’ coverage of HbA1c and other screening tests is an extremely positive change. Additional coverage may stop these patients from living with an undiagnosed condition for years, allowing them to receive treatment and begin lifestyle changes to improve their health sooner.

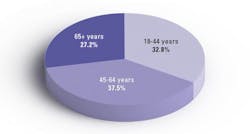

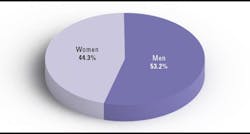

CDC National Diabetes Statistics

Identifying at-risk individuals before a prediabetes diagnosis

Yet there is still more that can be done. While HbA1c testing has been commonplace for years when diagnosing and treating diabetes and other metabolic conditions, certain other markers have shown to be effective in not only identifying risk of diabetes, but other related conditions, like cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease. These markers may not yet be mainstream lab tests, despite being widely prevalent among individuals.

One such test is insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is a condition that prevents the body from responding correctly to insulin, making a person unable to use glucose from the blood for energy. It is often the first stage in metabolic abnormalities that eventually may evolve, with age and weight gain, to prediabetes and then to type 2 diabetes. A recent analysis of 6,000 young adults, ages 18–44, found 40% have insulin resistance.10 Among experts, it is thought to be a precursor not only to the development of diabetes, but also other cardiovascular events, like potentially fatal heart attacks or strokes.

Certain new studies have emphasized the ability of insulin resistance to identify a patient’s risk of diabetes, even when their fasting blood sugar test is reported in a normal range.11,12 This research also found that the combination of HbA1c testing with insulin resistance can be a powerful prognostic tool for risk assessment, effectively identifying patients likely to develop prediabetes and diabetes before these conditions have become evident by laboratory testing. Furthermore, a number of other studies have examined (and continue to examine) the value of using combinations of glycemic biomarkers like fasting blood sugar, HbA1c, and others to improve risk assessment of cardiometabolic outcomes.13

As certain biomarkers and, more importantly, combinations of biomarkers can lead to improvements in risk prediction for cardiovascular disease and diabetes, expanding coverage and availability of testing beyond HbA1c will be key to improving the health of Americans nationwide. While the inclusion of HbA1c testing is a step in the right direction, there is so much more that can be done. Maintaining the availability of fasting blood sugar testing in combination with HbA1c, and widening the adoption of other tests to assess insulin resistance, will be critical to identifying individuals in need of treatment as early as possible. And the sooner these people become aware of their conditions, the sooner they can begin managing them.

Conclusion

With diabetes impacting so many individuals across America, it is hard to see greater availability of screening tools as anything but a net positive. However, we can and should do more. Providing diagnostic insights to patients is extremely important. Without the knowledge provided by lab testing, physicians will lack the complete picture of an individual’s health needed to craft a care plan. And patients may lack the motivation to seek care if they are unaware of their risk, potentially worsening underlying conditions and making it more likely they will suffer irreversible harm.

The inclusion of HbA1c testing as a diabetic screening measure by CMS will certainly benefit many at-risk individuals. But broadening coverage to include biomarkers like insulin resistance will allow physicians to test for combinations with the best ability to predict future risk, including of other cardiometabolic conditions. Like with so many diseases, providing treatment as soon as possible is critical to giving patients the best care. Testing early provides the insight needed to embark on the next steps of a care journey some at-risk individuals may be unable to prolong.

The research has been clear. The tools to predict risk are here, and growing in sensitivity and specificity. Why not utilize them to the best of their ability, and get more Americans with undiagnosed prediabetes screened to encourage them to take action?

References

1. Calendar year (CY) 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Cms.gov. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2024-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule.

2. American Medical Association. Pay schedule contains AMA advocacy wins on telehealth, diabetes. American Medical Association. Published September 29, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/pay-schedule-contains-ama-advocacy-wins-telehealth-diabetes.

3. CDC. All about your A1C. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published September 19, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/managing-blood-sugar/a1c.html.

4. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S62-9. doi:10.2337/dc10-S062.

5. CDC. Type 2 diabetes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published November 12, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/type2.html.

6. Hilborne LH, Bi C, Radcliff J, Kroll MH, Kaufman HW. Contributions of Glucose and Hemoglobin A1c Measurements in Diabetes Screening. Am J Clin Pathol. 2022;6;157(1):1-4. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqab106.

7. Jesudason DR, Dunstan K, Leong D, Wittert GA. Macrovascular risk and diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes: implications for the use of FPG and HbA(1c) for cost-effective screening. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(2):485-90. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.2.485.

8. CDC. Prediabetes - your chance to prevent type 2 diabetes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published November 12, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html.

9. Connecting SDOH and HRSN to prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. National DPP Coverage Toolkit. Published July 14, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://coveragetoolkit.org/health-equity-and-the-national-dpp/connecting-sdoh-and-hrsns-to-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes/.

10. Jones A. UAB researchers find that 40 percent of young American adults have insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors. UAB News. Published September 20, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uab.edu/news/research/item/12289-uab-researchers-find-that-40-percent-of-young-american-adults-have-insulin-resistance-and-cardiovascular-risk-factors.

11. Rooney MR, Daya NR, Leong A, et al. Prognostic value of insulin resistance and hyperglycemia biomarkers for long-term risks of cardiometabolic outcomes. J Diabetes Complications. 2023;37(9):108583. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2023.108583.

12. Meigs JB, Porneala B, Leong A, et al. Simultaneous Consideration of HbA1c and Insulin Resistance Improves Risk Assessment in White Individuals at Increased Risk for Future Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e90-e92. doi:10.2337/dc20-0718.

13. Bachmann KN, Wang TJ. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: contributions to risk prediction in individuals with diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61(5):987-995. doi:10.1007/s00125-017-4442-9.

About the Author

Michael J. McPhaul, MD

is a Medical Advisor at Quest Diagnostics and an expert on the interconnection of cardiometabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, diabetes and CVD. In his role at Quest, Dr. McPhaul drives the development of new tools and diagnostic tests that assist in the comprehensive care of patients with prediabetes, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus, as well as the early identification of these ailments. Dr. McPhaul earned his medical degree from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. He completed his internship and residency in internal medicine at Parkland Memorial Hospital, followed by a research fellowship in biochemistry at Stanford University Medical Center. Dr. McPhaul is board-certified by American Board of Internal Medicine. He is an active member of several professional societies, including the American Society of Clinical Investigation, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Endocrine Society, American Diabetes Association, Southern Society for Clinical Investigation, and the American Federation for Medical Research.