The rate of new cases of diagnosed diabetes in the United States has begun to fall, but the numbers are still very high. More than 29 million Americans are living with diabetes, and 86 million are living with prediabetes, a serious health condition that increases a person’s risk of type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases.1

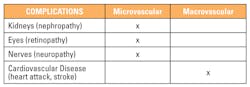

Diabetes can be a devastating disease with complications arising from uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Prevention, early detection, and monitoring of these potential complications are important to ensuring quality of life for patients with diabetes. The physiologic complications of diabetes can be diverse, but are generally separated into microvascular (small blood vessel-related) and macrovascular (large blood vessel-related) types. Some examples of the different types of micro- and macrovascular complications are listed in Table 1. All of these complications can be treated effectively if they are diagnosed at an early stage. This may be achieved by returning blood glucose concentrations to near-normoglycemic levels for a sustainable period. Intensive diabetes management with the goal of achieving near-normoglycemia has been shown in large prospective randomized studies to delay the onset and progression of morbidity and mortality associated with the

diabetic patient.2

According to the American Diabetes Association, diabetes may be diagnosed based on plasma glucose criteria, either the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or the 2-h plasma glucose (2-h PG) value after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or hemoglobin A1C criteria.3 There is a spectrum of clinical scenarios in diabetes, and it may be identified anywhere along the spectrum of those scenarios. For example, diabetes may be identified in seemingly low-risk individuals who happen to have glucose testing, in individuals tested based on diabetes risk assessment, and in symptomatic patients.3 Regardless of the scenario, the identification of hyperglycemia using laboratory tests is a common denominator.

Nephropathy

Increased urinary albumin excretion and reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in patients with diabetes are indicative of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetic kidney disease occurs in 20 percent to 40 percent of patients with diabetes and is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). In 2011, diabetes was listed as the primary cause of kidney failure in 44 percent of all new cases, and almost 50,000 people of all ages began treatment for kidney failure due to diabetes.

In diabetic nephropathy, cells and blood vessels in the kidneys are damaged, affecting the organs’ ability to filter out waste. The damage has been demonstrated to be a multi-layer physiologic process of occurrences brought on by elevated glucose concentrations in the blood. First, mesangial (cells that make up the glomerular mesangium, or structure associated with the glomerular capillaries) expansion is directly induced by hyperglycemia. It has been suggested that hyperglycemia may increase matrix production or glycation of matrix proteins, resulting in this expansion. Second, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane occurs. Third, glomerular sclerosis is caused by intraglomerular hypertension. Hypertension, along with increases in intraglomerular capillary pressure and metabolic abnormalities such as dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia, likely interact to accelerate renal injury.4 As a result of these homeostatic renal disturbances, waste builds up in the blood instead of being excreted. In some cases this can lead to kidney failure. The direct consequence of kidney failure is the need for dialysis filtration or, in the most severe cases, renal transplantation.5

Recommended interventions for kidney disease vary according to guidelines, but include achieving and maintaining near-normoglycemia,2 reducing blood pressure,6 and combination therapy of prescription drugs.7

Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is a highly specific vascular complication of diabetes. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is strongly related to the duration of diabetes. For example, diabetic retinopathy is the most frequent cause of new cases of blindness among adults aged 20–74 years.8 Glaucoma, cataracts, and other disorders of the eye occur earlier and more frequently in people with diabetes. Conversely, complications may worsen if glucose concentrations remain uncontrolled. Comorbidities and additional risk factors, such as smoking or high blood pressure, may exacerbate an already deleterious clinical situation in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes. Recommendations for prevention of diabetic retinopathy closely parallel those for prevention of diabetic nephropathy: optimize glycemic and blood pressure control. Eye examinations should be performed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist who is knowledgeable and experienced in diagnosing diabetic retinopathy.

Neuropathy

About 60 percent to 70 percent of people with diabetes have some form of neuropathy. Diabetic neuropathy is the result of nerve ischemia due to microvascular disease, direct effects of hyperglycemia on neurons, and intracellular metabolic changes that impair nerve function. Neuropathy can affect nerves throughout the body, causing numbness and sometimes pain in the hands, arms, and legs, and problems with the digestive tract, heart, sex organs, and other body systems. People with diabetes can develop nerve problems at any time, but risk rises with age and longer duration of diabetes. The highest rates of neuropathy are among people who have had diabetes for at least 25 years.9

Management of neuropathy involves a multidimensional approach including glycemic control, regular foot care, and management of pain. Strict glycemic control may lessen neuropathy.

Cardiovascular

The impact of macrovascular complications is overwhelming. The link between diabetes and heart disease is well established. Diabetes, both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, by itself is considered an independent risk factor for heart disease. Heart failure and peripheral arterial disease are the most common initial manifestations of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Ischemic stroke, stable angina, and non-fatal myocardial infarctions are also closely associated comorbidities. Approximately 65 percent of deaths among people with diabetes are caused by coronary artery disease or cerebrovascular disease.10 The death rate from coronary artery disease and risk for cerebrovascular disease is ~two to four times higher among people with diabetes than those without diabetes. The risk for developing cerebrovascular disease is also ~two times higher in people with diabetes as compared to those without diabetes. Peripheral vascular disease is a risk factor for lower limb amputation, and greater than 60 percent of all non-traumatic lower limb amputations occur in patients with diabetes.11

Blockage of the coronary arteries that occurs with coronary artery disease can lead to the development of acute coronary syndromes, a constellation of clinical symptoms caused by myocardial ischemia such as angina, unstable angina, and myocardial infarction resulting from coronary thrombosis or occlusion. When vessels supplying the brain become blocked, transient ischemic attacks or strokes can occur. Two types of strokes can develop: ischemic strokes resulting from cerebral thrombosis or occlusion, and hemorrhagic strokes resulting from rupture of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation. Blockage of vessels that supply the lower extremities can cause ischemia and infarction that result in leg pain and gangrene.

General screening, prevention, and treatment measures for macrovascular disease include assessment of risk, glycemic control using American Diabetes Association or American College of Endocrinology guidelines, blood pressure control, lipid control according to national guidelines, and lifestyle modification.

Diabetes is a treatable disease. However, uncontrolled diabetes can lead to devastating complications. Early identification of contributing predisposing risk factors and major risk factors can enable the implementation of effective strategies to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality of patients diagnosed with diabetes. Glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid control are essential to the prevention and management of micro- and macro-vascular complications.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes: working to reverse the US epidemic at a glance 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/diabetes.htm.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications (DCCT) Research Group; Effect of intensive therapy on the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Kidney Int. 1995;47(6):1703–1720.

- Diabetes Care. 2016;39 (Suppl. 1):S13–S22 | DOI: 10.2337/dc16-S005).

- Batuman V, Soman A. Diabetic Nephrology. Medscape. September 30, 2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/238946-overview.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevent complications. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/problems.html.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998;317:703–713.

- Parving H-H, Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Hollenberg NK; AVOID Study Investigators. Aliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. NEJM. 2008;358:2433–2446.

- Diabetes Care.2015;38(Suppl. 1):S58–S66.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Nerve damage (diabetic neuropathies): https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/preventing-diabetes-problems/nerve-damage-diabetic-neuropathies.

- Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, et al. American Heart Association. AHA Scientific Statement: Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. 1999. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/100/10/1134.

- American Diabetes Association; Statistics About Diabetes http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statisticks/?referrer=https://www.google.com/.

Ross Molinaro, PhD, MLS(ASCP)CM, DABCC, FACB, serves as Head of Medical Affairs & Medical Officer for Siemens Healthineers.

Carole Dauscher serves as Senior Manager, Global Marketing, Thyroids and Diabetes, for Siemens Healthineers.

Buildup of “toxic fat” metabolite could increase diabetes risk

For years, scientists have known that someone who is thin could still end up with diabetes. Yet an obese person may be surprisingly healthy.

Now, new research led by scientists at the University of Utah College of Health, and carried out with an international team of scientists, points to an answer to that riddle: accumulation of a toxic class of fat metabolites, known as ceramides, may make people more prone to type 2 diabetes.

Among patients in Singapore receiving gastric bypass surgery, ceramide levels predicted who had diabetes better than obesity did. Even though all of the patients were obese, those who did not have type 2 diabetes had less ceramide in their adipose tissue than those who were diagnosed with the condition.

“Ceramides impact the way the body handles nutrients,” says the study’s senior author, Scott Summers, PhD. “They impair the way the body responds to insulin, and also how it burns calories.”

In the study, published Nov. 3 in Cell Metabolism online, the researchers also show that a buildup of ceramides prevents the normal function of fat (adipose) tissue in mice.

When people overeat, they produce an excess of fatty acids. Those can be stored in the body as triglycerides or burned for energy. However, in some people, fatty acids are turned into ceramides. “It’s like a tipping point,” Summers says.

At that point, when ceramides accrue, the adipose tissue stops working appropriately, and fat spills out into the vasculature or heart and does damage to other peripheral tissues. Until now, scientists didn’t know how ceramides were damaging the body.

The three-year project found that adding excess ceramides to fat cells caused mice to become unresponsive to insulin and develop impairments in their ability to burn calories. The mice were also more susceptible to diabetes as well as fatty liver disease.

Conversely, researchers also found that mice with fewer ceramides in their adipose tissue were protected from insulin resistance, a first sign of diabetes. Using genetic engineering, researchers had deleted the gene that converts saturated fats into ceramides.

The findings indicate that high ceramides levels may increase diabetes risk and low levels could protect against the disease. The scientists think this could mean that some people are more likely to convert calories into ceramides than others. “That suggests some skinny people will get diabetes or fatty liver disease if something such as genetics triggers ceramide accumulation,” says Bhagirath Chaurasia, PhD, lead author of the study.

As a result of the new research, the scientists are now searching for genetic mutations that lead to people’s predisposition to accumulating ceramides and developing obesity and type 2

diabetes.

“By blocking ceramide production, we might be able to prevent the development of type 2 diabetes or other metabolic conditions, at least in some people,” Chaurasia says. Knowing how problematic ceramide accumulation is inside adipose tissue will help researchers focus on that specific problem.