A combination of esophageal brushing and extensive genetic sequencing of the sample collected can detect chromosome alterations in people with Barrett’s Esophagus, identifying patients at risk for progressing to esophageal cancer, according to a new study by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and Case Western Reserve University as reported in a news release.

Results were published online in the journal Gastroenterology.

In Barrett’s Esophagus (BE), chronic acid reflux from the stomach damages the cells lining the lower esophagus, causing them to become more like cells of the lower digestive system. Cells in the lower esophagus progress through several precancerous stages before sometimes developing into esophageal adenocarcinoma, a cancer with a five-year survival rate below 20 percent. BE is the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Clinicians can detect these progressive states in BE by looking for chromosomal alterations known as aneuploidy – a common feature in most cancer cells – but until now the process has involved multiple biopsies.

A single esophageal brushing paired with the sequencing technique called RealSeqS is sensitive and specific enough to identify aneuploidy at several stages of BE progression, and can even match specific types of aneuploidy with specific stages of the disease, the researchers say.

“Aneuploidy has long been implicated in the development, initiation or progression of esophageal cancer, but the assays or experimental methods to detect this have not been as easily achieved or as high throughput as we would have wanted to allow for clinical implementation,” says Senior Study Author Chetan Bettegowda, MD, PhD, Jennison and Novak Families Professor of Neurosurgery at the Kimmel Cancer Center.

Esophageal brushing uses a soft brush attachment for an endoscope to collect cells from the esophageal lining. The method can sample cells from a larger surface area of the esophagus than a usual biopsy. Endoscopy, often with brushing, “is part of the standard of care for people who have Barrett’s,” Bettegowda says, so incorporating the aneuploidy detection method would not change substantially change clinical practice.

Only a few cells out of hundreds sampled through brushing may demonstrate aneuploidy, however, so combining brushing with massively parallel sequencing is key to finding these cells. The researchers used a technique called RealSeqS to look across more than 350,000 regions of the genome to identify specific chromosome arm alterations. RealSeqS can typically detect aneuploidy at the level of about 1 in 200 cells, which is necessary when large portions of the esophageal brushing are derived from normal cells, says study lead author Christopher Douville, the Kimmel Center researcher who designed RealSeqS.

The researchers obtained esophageal brushings from patients without BE, with BE and no abnormal cells, with BE and either low or high-grade cell abnormalities, and patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. They trained their identification system to distinguish brushings from BE patients without cell abnormalities from those with adenocarcinoma using samples from 79 patients.

The research team then looked at samples from 268 patients to test whether the method could distinguish different stages of BE progression.

Bettegowda, Douville and their colleagues identified a threshold of aneuploidy that distinguished patients with high-grade cell abnormalities and adenocarcinoma from BE patients with no cell abnormalities. At this threshold, the method identified high-risk patients in 232 or 86.7% of cases.

The method also identified specific chromosomal arm changes at each stage of BE progression toward adenocarcinoma. Some of these specific changes have already been linked to disease stages by previous research, “but they were not comprehensive enough to be used in some diagnostic or prognostic way,” says Douville.

The researchers used these changes to develop an assessment tool they called BAD (Barrett’s Aneuploidy Decision), for distinguishing stages of BE progression. The tool could be especially useful for identifying high-risk individuals when cell biopsies look benign, because the BAD tool points out molecular changes that are linked to more aggressive disease, Bettegowda says.

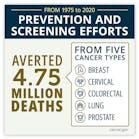

“Aneuploidy is as universal a biomarker as we can find at the moment for cancer, so we are excited to see how we can employ this technology for a multitude of cancers,” he says. “We are optimistic that given the versatility of the RealSeqS assay that we could study other disease processes, other cancer types and potentially find other ways to intervene earlier.”