Phages are key to emergence of “superbugs” and their treatment

For the first time ever, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine discovered that phages—tiny viruses that attack bacteria—are key to initiating rapid bacterial evolution leading to the emergence of treatment-resistant “superbugs.” The findings were published in Science Advances.

The researchers showed that, contrary to a dominant theory in the field of evolutionary microbiology, the process of adaptation and diversification in bacterial colonies doesn’t start from a homogeneous clonal population. They were shocked to discover that the cause of much of the early adaptation wasn’t random point mutations. Instead, they found that phages, which we normally think of as bacterial parasites, are what gave the winning strains the evolutionary advantage early on.

“Essentially, a parasite became a weapon,” said senior author Vaughn Cooper, PhD, Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics at Pitt. “Phages endowed the victors with the means of winning. What killed off more sensitive bugs gave the advantage to others.”

When it comes to bacteria, a careful observer can track evolution in the span of a few days. Because of how quickly bacteria grow, it only takes days for bacterial strains to acquire new traits or develop resistance to antimicrobial drugs.

The new study shows that bacterial and phage evolution often go hand in hand, especially in the early stages of bacterial infection. This is a multilayered process in which phages and bacteria are joined in a chaotic dance, constantly interacting and co-evolving.

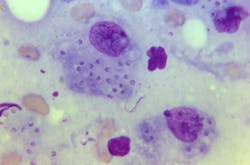

When the scientists tracked changes in genetic sequences of six bacterial strains in a skin wound infection in pigs, they found that jumping of phages from one bacterial host to another was rampant—even clones that didn’t gain an evolutionary advantage had phages incorporated in their genomes. Most clones had more than one phage integrated in their genetic material—often there were two, three or even four phages in one bug.