Women face diverse and unique health concerns that can affect their overall health and wellness. Additionally, women are more prone to certain infectious, autoimmune, and mental health diseases than men. For example, genital herpes from herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2) is nearly twice as common among women than in men; women account for more cases of chlamydia, lupus, and scleroderma compared to men;1 and community studies show that women have about two to three times higher risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their lifetime compared to men.2 There are also diseases that affect only women such as cervical cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and Rett syndrome.3 For some diseases, women face complications or more dire consequences than seen in men infected with the same causative agent. For example, women with HIV are at a higher risk of severe cases of gynecological problems, such as chlamydia or bacterial vaginosis, than are noninfected women.

Women also risk passing some diseases, such as HIV, to children during pregnancy or breastfeeding.1 Women can also run the risk of passing group B streptococcus (GBS) to newborns. One in four pregnant women are believed to be carrying GBS in the intestine and genital tract without any symptoms. However, when they are passed on to the newborn, the bacteria may cause bloodstream infections or serious diseases like meningitis in the newborn within the first three months of life. 4%–6% of babies who develop GBS disease die.4

Importance of molecular diagnostics in women’s health

A molecular diagnostic technique was first used in 1976 to make a prenatal diagnosis of α-thalassemia.5

Since then, molecular diagnostics have undergone a period of rapid development and growth. With the emergence of new high complexity tests and integration of new technologies, clinical laboratories have introduced molecular diagnostics in various fields such as infectious diseases, genetics, pharmacogenomics, and oncology.

Molecular diagnostics techniques including nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR, or strand displacement amplification (SDA) have high sensitivity and specificity with rapid turnaround time compared to many nonmolecular techniques. Thus, they are more often preferred over cell culture, fluorescent antigen-antibody detection, and immunoassays — especially for diagnosing bacterial or viral infections.

High-throughput methods, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) or genome-wide association studies, provide invaluable insights into the mechanisms of disease, and genomic biomarkers allow physicians to not only assess disease predisposition but also to design and implement accurate diagnostic methods and to individualize therapeutic treatment modalities.6

Using NAAT to diagnose infections and disease

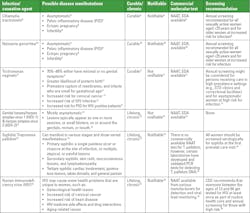

Sexually transmitted infections: Young women’s bodies are biologically more prone to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).7 The common sexually transmitted infections are caused by chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas,8 genital herpes, human papillomavirus (HPV), syphilis, and HIV.7 Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Trichomonas vaginalis cause substantial health losses among women in the United States.8 Chlamydia and gonorrhea cause the two most frequently reported bacterial infectious diseases in the United States, and prevalence is highest among persons aged ≤24 years. Table 1 provides details on the various sexually transmitted infections.

Vaginosis/vaginitis: This is the most common cause of vaginal infections and discharge among women ages 15–44. It has been associated with preterm birth and contracting sexually transmitted infections, such as HIV and pelvic inflammatory disease. It can be caused due to infections from bacteria (bacterial vaginosis), yeasts (vaginal candidiasis /vulvovaginal candidiasis), protozoan parasite, Trichomonas vaginalis (Trichomoniasis), or non-infectious vaginitis (atrophic vaginitis) caused by allergic reactions from vaginal sprays, douches, or spermicidal products.15

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused due to reduction in lactobacilli and increase in diverse anaerobic and facultative bacteria in the vaginal microbiome.16 Candida vaginitis (CV) or vulvovaginitis that leads to inflammation of vulva and vagina is caused majorly due to Candida albicans or at times due to non-C, albicans yeasts such as C. glabrata, C tropicalis, C parapsilosis, C krusei, C. dubliniensis. There are a few commercially available molecular tests that detect bacterial vaginitis and candida vaginitis simultaneously. Several clinical laboratories have also developed validated molecular tests to detect some of the bacteria and Candida species.17

Cervicitis: It is an infection of the cervix and can be caused due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus, or Mycoplasma genitalium. Cervicitis can be asymptomatic or show symptoms such as purulent discharge, pelvic pain, bleeding between periods or after sexual intercourse or urinary problems.18, 19 Commercial molecular tests (NAAT) are available to detect the organisms that can cause cervicitis.

Group B streptococcus (GBS): About 1 in 4 pregnant women carries GBS bacteria in their body. As GBS can cause serious infections if passed to the newborns, pregnant women need to get tested for GBS bacteria when they are 36 through 37 weeks pregnant.20 Commercial molecular tests are available for GBS.

Cervical cancer: Cervical cancer (CC) is a group of invasive epithelial neoplasms of the cervix, which have metastatic potential. 70% of CC are squamous cell carcinoma and 25% adenocarcinoma, with the remainder rare tumors, such as small cell carcinoma.21 99% of CC cases are caused due to persistent infection with high-risk human papilloma virus (HR-HPV).21 There are as many as 15 HR-HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), and globally, HPV 16 is the most frequent oncogenic type. HPV types 16 and 18 have been found to cause 75% of cervical cancer cases.22,23 Approximately 7000 patients die from it yearly. That said, not every patient with HPV precancerous lesions will progress to CC.22

A patient with HR-HPV infection goes through various stages over the years to develop CC.

Early screening, ongoing surveillance, and accurate diagnosis are crucial for the elimination of CC.24

Screening refers to testing for disease among individuals who are asymptomatic, have not been tested previously, or have normal prior results, and the strategies can be primary HPV screening, co-testing with HPV testing and cervical cytology, or cervical cytology alone.24

Surveillance is the interval testing among individuals who had a prior abnormal result, with or without treatment. The 2019 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines describe clinical actions that providers can use when managing patients with abnormal cervical cancer screening test results.25

Several commercially available molecular tests are available that detect HR-HPV and genotype HPV 16 and 18 that can be used for screening and surveillance for CC. Diagnosis of cervical cancer involves colposcopy and biopsy.24Using Sequencing/NGS technique or genome-wide studies

Breast cancer: Molecular testing for genetic and genomic variation has become an integral part of breast cancer management.26 About 3% of breast cancers (about 7,500 women per year) result from inherited mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.27 Per the Consensus Guideline on Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer put forth in 2019 by the American Society of Breast Surgeons, genetic testing should be made available to all patients with a personal history of breast cancer. The genetic testing should include BRCA1/BRCA2 and PALB2 and other genes as appropriate for the clinical scenario and family history.28 With the advancements in next-generation sequencing technology, it is possible to test a panel of other genes; however, their clinical significance are not yet certain and no actionable recommendation are available.28

Ovarian cancer: It is estimated that up to 25% of ovarian cancers are hereditary.29 Mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes account for most hereditary ovarian cancers and 10% – 15% of all ovarian cancer diagnoses. Researchers are continuing to investigate genetic mutations, both inherited and acquired, that may increase the risk of cancer. Studies are emerging that link ovarian cancer with mutations in other genes involved in DNA repair, including RAD51C, RAD51D, BRIP1, PALB2 (which stands for partner and localizer of BRCA2), STK11, ATM.29

Rett Syndrome: Rett syndrome (RTT) is an early-onset neurodevelopmental disorder that almost exclusively affects girls and is totally disabling. Three genes have been identified that cause RTT: MECP2, CDKL5, and FOXG1.30 Next generation sequencing (NGS) has promoted genetic diagnoses because of the quickness and affordability of the method.Conclusion

Detection and treatment of women’s health issues received a big boost with the developments in molecular diagnostics. These molecular diagnostic tests give laboratory professionals and healthcare providers the power to assess a wide range of women’s health conditions. Continued research in the field of genomics and proteomics and emergence of newer technologies will lead to further improvement in screening, surveillance, and diagnosis of women’s health-related diseases.

References

1. Women’s health. Nih.gov. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/womens-health.

2. Kimerling R, Weitlauf JC, Iverson KM, Karpenko JA, Jain S. Gender issues in PTSD. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA, eds. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. Guilford Press; 2013.

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). Female-Specific Diseases. National Center for Biotechnology Information; 1998.

4. Fast facts. Cdc.gov. Published October 18, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep/about/fast-facts.html.

5. Molecular diagnostics in the medical laboratory in real time. Asm.org. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://asm.org/Articles/2021/July/Molecular-Diagnostics-in-the-Medical-Laboratory-in.

6. Patrinos GP, Ansorge WJ, Danielson PB. Preface, Third Edition. In: Molecular Diagnostics. Elsevier; 2017:xvii-xviii.

7. Adolescents and STDs. Cdc.gov. Published June 30, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/life-stages-populations/stdfact-teens.htm.

8. Li Y, You S, Lee K, Yaesoubi R, et al. The Estimated Lifetime Quality-Adjusted Life-Years Lost Due to Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Trichomoniasis in the United States in 2018. J Infect Dis. 2023;18;227(8):1007-1018. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiad047.

9. Chlamydial infections. Cdc.gov. Published August 15, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/chlamydia.htm.

10. Gonococcal infections among adolescents and adults. Cdc.gov. Published December 5, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/gonorrhea-adults.htm.

11. Trichomoniasis. Cdc.gov. Published September 21, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/trichomoniasis.htm.

12. Detailed STD facts - genital Herpes. Cdc.gov. Published June 28, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm.

13. Syphilis. Cdc.gov. Published April 14, 2023. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm.

14. How does HIV impact women’s health? Hiv.gov. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/staying-in-hiv-care/other-related-health-issues/womens-health-issues/.

15. Vaginitis. Hopkinsmedicine.org. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/vaginitis.

16. Coleman JS, Gaydos CA. Molecular Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis: an Update. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;27;56(9):e00342-18. doi:10.1128/JCM.00342-18.

17. Lillis RA, Parker RL, Ackerman R, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new molecular test for the detection of organisms causing vaginitis and vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61(3). doi:10.1128/jcm.01748-22.

18. Urethritis and cervicitis - STI Treatment Guidelines. Cdc.gov. Published September 21, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/urethritis-and-cervicitis.htm.

19. Cervicitis. Hopkinsmedicine.org. Published November 19, 2019. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/cervicitis.

20. Diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Cdc.gov. Published October 18, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep/about/diagnosis.html.

21. Kurman RJ. International agency for research on cancer, world health organization. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. In: International Agency for Research on Cancer.;2014.

22. Amin FAS, Un Naher Z, Ali PSS. Molecular markers predicting the progression and prognosis of human papillomavirus-induced cervical lesions to cervical cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Mar 31. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-04710-5.

23. Williams J, Kostiuk M, Biron VL. Molecular Detection Methods in HPV-Related Cancers. Front Oncol. 2022;27;12:864820. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.864820.

24. Zhu Y, Feldman S, Leung SOA, Creer MH, et al. AACC Guidance Document on Cervical Cancer Detection: Screening, Surveillance, and Diagnosis. J Appl Lab Med. 2023;6;8(2):382-406. doi:10.1093/jalm/jfac142.

25. Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, Demarco M, et al. Risk Estimates Supporting the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(2):132-143. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000529.

26. Litton JK, Burstein HJ, Turner NC. Molecular testing in breast cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39(39):e1-e7. doi:10.1200/EDBK_237715.

27. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Cdc.gov. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/breast_ovarian_cancer/genes_hboc.htm.

28. Manahan ER, Kuerer HM, Sebastian M, Hughes KS, et al. Consensus Guidelines on Genetic` Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer from the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3025-3031. doi:10.1245/s10434-019-07549-8.

29. Genetic mutations in ovarian cancer. OCRA. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://ocrahope.org/get-the-facts/genetic-testing/.

30. Vidal S, Brandi N, Pacheco P, et al. The utility of Next Generation Sequencing for molecular diagnostics in Rett syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12288. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11620-3.About the Author

Rajasri Chandra, MS, MBA

is a global marketing leader with expertise in managing upstream, downstream, strategic, tactical, traditional, and digital marketing in biotech, in vitro diagnostics, life sciences, and pharmaceutical industries. Raj is an orchestrator of go-to-market strategies driving complete product life cycle from ideation to commercialization.