Raising awareness of group B streptococcal disease (GBS) among pregnant women and women who are of child-bearing age is an important component in the effort to prevent a potentially fatal infection in neonates. Clinical laboratorians play an important role in educating patients about current testing methods—the centerpiece of the GBS awareness puzzle.

What is GBS?

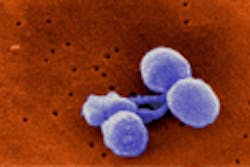

S. agalactiae or group B Streptococcus is a gram-positive bacteria commonly found in the gastrointestinal, genital, and urinary tract of healthy adults. Approximately 25 percent of all pregnant women are colonized with GBS. While colonized mothers typically show no symptoms or adverse health effects, the bacteria can be passed to their children during labor and delivery. The fatality rate for infants with early-onset GBS disease is currently estimated at four percent to six percent. Surviving infants may experience long-term disabilities including hearing loss, vision loss, or mental retardation. If detected, transmission of GBS can be prevented by administration of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to delivery.

What do the guidelines say about testing?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all pregnant women between 35 and 37 weeks gestation be tested for GBS.1 Women who test positive should be given prophylactic antibiotics during labor, which will usually prevent transmission to the infant. GBS colonization status should be determined by collecting both vaginal and rectal specimens at 35 to 37 weeks. A single combined vaginal-rectal specimen can be collected if preferred.

What is the traditional way to detect GBS?

Detection of GBS may be accomplished using various testing algorithms, media, and methodologies. Direct plating has a lower sensitivity than enriched culture and should not be used as a sole means of isolation and identification. To maximize the recovery of GBS, all specimens should undergo an 18-to-24-hour incubation at 35° to 37°C in an appropriate enrichment broth medium, such as carrot or Lim broth.

The traditional method of testing is to inoculate an enrichment broth with the vaginal-rectal swab sample and plate the incubated enriched broth on a blood agar plate (BAP). The BAP is incubated and examined for growth of beta-hemolytic colonies. Suspicious colonies are sub-cultured and tested by latex agglutination for identification.

This method presents challenges. There are strains of GBS that are non-hemolytic. These strains mimic the appearance of enterococcus and can be easily overlooked when reading plates. Studies have shown that sensitivity of culture can be as low as 42 percent.2 Specimens that are enhanced in chromogenic broth or plated to chromogenic media present a similar challenge with regard to detection of non-hemolytic strains of GBS. Approximately five percent of human-colonizing GBS isolates are reported non-hemolytic and non-pigmented.3 According to a 2009 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine,4 61.4 percent of term infants with GBS disease were born to women who tested negative for GBS before delivery, and 99.5 percent of these mothers were tested with traditional culture.

What role can NAAT play?

The limitation of culture is but one aspect of the problem. In addition, suboptimal specimen collection methods and/or lower levels of colonization may be contributing to false negative results. For this reason, the most sensitive assay should be used to optimize results. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) may be beneficial in confirming true positives in women with lower levels of GBS in the collected specimen. Testing via NAAT removes the subjectivity from culture testing and provides a greater level of confidence in test reports.

The ramifications of not detecting group B Streptococcus in a pregnant mother can be devastating. Testing with a molecular assay can protect newborns from suffering serious GBS-related complications. Early-onset GBS infection in neonates is a grave, yet preventable, disease. NAAT can serve a crucial role as a confirmatory test for positive cultures. Many laboratory leaders are currently reviewing their current testing protocols and making changes as necessary.

By the way, Group B Streptococcus Awareness Month is just around the corner—it’s July. Why not plan an awareness event for lab staff, the larger institution, or the community!

REFERENCES

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease, revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR. 2010:59.

- Rallu F, Barriga P, Scrivo C, Martel-Laferrière V, Laferrière C. Sensitivities of antigen detection and PCR assays greatly increased compared to that of the standard culture method for screening for group B Streptococcus carriage in pregnant woman. J Clin Microbiol. 44(3) 725-728.

- Rodriguez-Granger J, Spellerberg B, Asam D, Rosa-Fraile M. Non-haemolytic and non-pigmented group B Streptococcus, an infrequent cause of early onset neonatal sepsis. FEMS Pathogens and Disease. 2015;73(9);1-3.

- Van Dyke M, Phares C, Lynfield R, et al. Evaluation of universal antenatal screening for group B Streptoccoccus. NEJM. 2009;360:2626-2636.

Jennifer W. Sayers, MHA, MT(ASCP), serves as a product manager for Cincinnati, Ohio-based Meridian Bioscience.