The AABB, The Joint Commission, and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) have required laboratories to have disaster plans for many years. Previously, the plans tended to focus on treating a large number of patients. However, events such as terrorist attacks, tornados, spring floods, wildfires, hurricanes, earthquakes, and influenza epidemics have led to healthcare facilities’ being unable to provide services. In addition, the failure of electrical or water services, the loss of computer systems, and the inability to obtain critical supplies have resulted in compromised patient care. Disaster planning has changed to emergency management to better reflect the wider scope of planning needed.

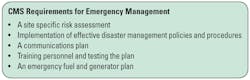

Emergency management is a comprehensive term. It includes how to prepare for, respond to, and recover from unanticipated events. In recognition of the need for more extensive planning for unexpected events. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) published requirements for Emergency Preparedness to ensure that healthcare facilities could operate in times of emergency and disasters (Table 1). Because the laboratory is a critical part of providing safe and effective patient care, the laboratory must plan ways to reduce the impact of emergency events. The goals of the new regulations for healthcare services are to safeguard human resources, maintain business continuity, and protect physical resources during emergencies. The new regulations will become effective on November 15, 2017. This article will review the major sections of the new CMS regulations as they apply to the laboratory.

Risk assessment

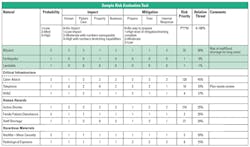

Each facility is required to evaluate the effect of specific potential internal and external events based on the likelihood of their occurrence and the level of disruption that is likely to occur should the event take place. The regulations do not require a specific format for the risk assessment. The laboratory should perform its own risk assessment in order to identify areas where procedures and training are needed. In the sample risk assessment grid (Table 2), disaster types are rated based on their probability of the event occurring, the impact of the event, and the amount of mitigation that has already been done to prepare for the event.

Probability of an event occurring can be based on history and an assessment of whether this event is more likely in the future. For example, the threat of an active shooter may not be great historically, but it has increased based on events occurring in other parts of the country.

The impact the event will have on human resources, patient care, property damage, and the continuity of business are rated on a scale of zero to three. For example, earthquakes in Michigan are infrequent, and so mild that they are often unnoticeable when they do occur. As such, that would rate as a one. However, in California, earthquakes’ effect on humans, patient care, property damage, and the ability to continue business functions is high, for a three rating.

Mitigation is evaluated based on how prepared the facility is to respond to the event. If there is no way to prepare for the event, the rating is zero. If there a robust plan, staff have been trained on how to respond, and the facility has internal resources to respond to the event, then the rating is one.

The next step is to multiply the rating numbers together to obtain a risk priority number (RPN). The higher the RPN, the greater the resources that need to be assigned to planning and training for the event.

Policies and procedures

Essential to planning is providing guidance to employees through policies and procedures. These plans must be available to staff during the emergency event. The plans are based on the risks identified in the risk assessment.

For example, the loss of water may cause equipment to be shut down and sanitation issues to arise. Electrical outages may change operations dues to less power and a loss of air-conditioning. While some equipment will shut down automatically if the room is too hot or humid, less sophisticated equipment will not. Policies and procedures for assessing continued operations are critical elements in the laboratory’s emergency management plan for flood, fire, failure of utilities, and any other event that may degrade laboratory operations.

Many labs have a list of tests that would be performed in an emergency event in order to provide critical care. However, are there agreements with other facilities and processes in place to transfer laboratory testing to another facility? What plans have been made to move a laboratory function to another area of the facility should there be compromise to the current laboratory?

Often overlooked in planning is staffing. Are staff trained and competent to work in other sections of the laboratory? What laboratory operations could be curtailed if there is an influenza epidemic? If staff are quarantined at work, what are the plans to house and feed them? Are there staff in other areas of the institution who could be used to perform non-testing activities in the laboratory? How would trained laboratory workers from outside the facility be integrated into the staff? How can the laboratory comply with state licensure laws and requirements for competency assessments?

Communications plan

The laboratory needs a communications plan for emergency events. How are laboratory staff members who are critical to providing patient care safely and effectively contacted during an emergency? How do staff members communicate with other healthcare providers to ensure the continuation of patient care? Communication disruptions range from cyberattacks that can crash or disable the laboratory or hospital’s computer systems to paging or telephone system outages. Telephone and paging fan-out lists need constant updating to remain useful. Because text messages are more likely to get through during an emergency, they should be considered as an addition to the backup communications plan. The fan-outs and phone/text numbers lists also need to be available to staff when staff are off-site. The list could be provided on paper or downloaded to cell phones. How could staff members be used to hand-carry messages and reports? For laboratories in large and complex buildings, do staff members know how to get to the emergency room, the ICU, and other locations within the facility?

Training and testing

Each facility is required to have an emergency management training and testing program. In addition to initial training, annual updating of emergency training is required. This training should include the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) as might be needed for specific events. The laboratory must participate in drills to identify gaps and areas needing improvement.

In addition to facility practice events, the laboratory should stage its own events. Table-top exercises that test policies and procedures and simulated events that test staff understanding as well as staff decision making do not take extensive planning and do identify needs for procedure revisions or additional staff training.

After a practice or real emergency event, a debriefing of the event that assesses staff interactions and decision making, resource needs, and procedure effectiveness is an important part of completing the event. The final step in reacting to a simulated or actual event is to act on any recommendations made.

Emergency fuel and generator plan

Unless your laboratory is off-site or an independent laboratory, hospital resources are responsible for the emergency fuel and generator plan.

The lab in an emergency

Defining the laboratory’s role in and response to emergency events is an important part of quality management. CMS now requires facilities to have plans, procedures, training, and testing events to ensure staff can function to provide effective and timely patient care in the event of an emergency. This plan should also provide a safe working environment for staff.

Because the laboratory provides critical information for patient care, it should design and implement emergency management plans to protect patients and staff.

RESOURCES

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Emergency Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers Federal Register 81 FR 63859 63859-64044. 09/16/2016 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertEmergPrep/Emergency-Prep-Rule.html.

- Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program, April 2013. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1914-25045-8890/hseep_apr13_.pdf.

- Healthcare COOP and Recovery Planning. Concepts, Principles, Templates and Resources. January 2015. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/reports/Documents/hc-coop2-recovery.pdf.

Suzanne H. Butch, MA, MLS(ASCP)CM SBBCM, DLMCM, CQA(ASQ), formerly served as Compliance Manager for the Department of Pathology and Administrative Manager for the Blood Bank and Transfusion Service of the University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers, Ann Arbor, MI. She has more than 40 years’ experience in blood banking, with special interests in barcoding and optimizing operations through computerization and the application of Lean principles.