Healthcare continues its shift from a volume-based to a value-based reimbursement structure. Because of the increasing emphasis on patient care beyond institutional walls, population health is a priority for healthcare leaders as they work toward “budgeted care.”

Due to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and efforts to reduce costs, laboratories of all types are focused on potentially declining reimbursements. Because the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has already seen some cost savings with alternative payment models, a combined total program savings of $417 million to Medicare due to existing Accountable Care Organization (ACO) programs,1 the reimbursement models for laboratory testing are trending toward further change, and it is important to understand the shift and its complexities. The ACA created a number of new payment models that drive the concept of rewarding quality.

In an unprecedented move, the Medicare program has set defined goals for alternative payment models and value-based payments. HHS’ goal is to tie 30 percent of traditional, or fee-for-service, Medicare payments to quality or value through alternative payment models by the end of 2016, and 50 percent of payments to these models by the end of 2018.1 Is your lab management team up to date on new payment models and their impact to your lab?

Alternative payment models

Here are thumbnail definitions of alternative payment models:

Accountable Care Organization (ACOs) are groups of healthcare providers and hospitals that jointly provide coordinated care of the patient population with the goal of giving higher quality while reducing the cost. Health information technology and the data it provides should help to measure the quality of these efforts.

Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH): This model marks a transition away from symptom-and-illness-based episodic care to a system of comprehensive coordinated primary care. Personal physicians are responsible for coordination of care across all healthcare systems facilitated by registries, information technology, health information exchanges (HIEs), and other means to ensure patients receive care when and where they need it. 2,3

ACOs can build on the coordinated care provided by the PCMHs and ensure and incentivize communications among teams of providers that operate in various settings. They can also develop and support systems for the coordination of care of patients in non-ambulatory care settings. In addition, they can monitor health information systems, timeliness, and completeness of information transactions between primary care physicians and specialists. The tracking of this information can be used to incentivize higher levels of responsiveness and collaborations.4

Due to the financial incentive to coordinate care in these alternative payment models, providers are less likely to order duplicative or unnecessary tests. Therefore, test and blood utilization initiatives become very important in these settings.

Bundled Payment: This model, also known as episode-based payment, ties provider reimbursement to clinically defined episodes of care. It has been described as “a middle ground” between fee-for-service reimbursement (in which providers are paid for each service rendered to a patient) and capitation (in which providers are paid a “lump sum” per patient regardless of how many services the patient receives).5 The reimbursement covers all the treatments and interventions performed over a full care cycle for an acute medical condition.

In addition to HHS setting payment goals related to alternative payment models, the agency has also suggested tying 85 percent of all traditional Medicare payments by 2016 and 90 percent by 2018 to quality or value through programs such as the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Programs.1

Medicare payment categories

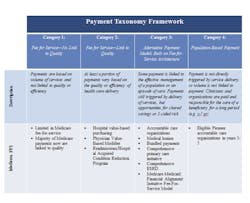

HHS has adopted a framework that categorizes healthcare payment according to how providers receive payment to provide care6 (Table 1):

Category 1—fee-for-service with no link of payment to quality

Category 2—fee-for-service with a link of payment to quality

Category 3—alternative payment models built on fee-for-service architecture

Category 4—population-based payment

In 2011, Medicare made almost no payments to providers through alternative payment models, but, due to reforms under the ACA and other changes, an estimated 20 percent of Medicare reimbursements had shifted to categories 3 and 4, directly linking provider reimbursement to the health and well-being of patients.6

This trend is estimated to continue with the explicit goals established by HHS for the near future (Figure 1).

Fee changes

In addition to this method of bundled payments, the Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule (CLFS) fee-for-service reimbursement amounts are also in for some impactful changes soon. Signed into law on April 1, 2014, the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 (PAMA) includes the most extensive reform of the CLFS since it was established in 1984. Medicare will reimburse labs based on market prices starting in 2017. By June 30, 2015 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was to have reported the first regulations that direct how the agency will collect private market data and set new CLFS rates. (As this issue of MLO goes to press, these have not yet been released).

Highlights of the CLFS reform provisions included in PAMA are as follows:

- Beginning in 2016, laboratories will be required to report extensive private payer pricing and volume information to CMS or face significant fines and penalties; private payer data is to be reported every three years.

- CMS will determine the CLFS payment to equal the weighted median prices of private payer rates, and these weighted medians will be the Medicare rates that are effective beginning on January 1, 2017.

- CLFS will no longer be subject to geographic adjustments, budget neutrality adjustments, annual updates, or “other adjustments.”

- At press time CMS was expected to finalize rules that explain how the agency will collect private market data and set new CLFS rates.

- Phase-in of payment reductions is limited to 10 percent for 2017 to 2019 and 15 percent for 2020 to 2022.

- Special provisions have been made for new tests and advanced diagnostic laboratory tests as well as for coding.

Patient type and reimbursement

The PAMA reimbursement changes will be highly impactful to outreach programs which are reimbursed from the CLFS. In this new healthcare environment, lab leaders should stay mindful, on the front-end of the testing process, of what constitutes an outreach patient type paid by the CLFS, as opposed to what is considered a hospital outpatient and paid via bundled reimbursement due to the Outpatient Perspective Payment System (OPPS). This is crucial for compliant billing and for maximizing compliant reimbursements. Under the OPPS regulation, Outpatient laboratory tests are generally packaged as ancillary services and do not receive separate payment, hence the advantage for outreach in growing this market.

For many labs, the OPPS rule of 2014 greatly impacted their definition of Outreach patients. Prior to this new ruling, hospitals had the option of defining Outpatients, with lab tests ONLY ordered, as a Non-Patient (NP) and of billing these patients on a 14X bill type along with the traditional pure outreach NPs. Previously, it was documented as such according to the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 6—Hospital Services Covered Under Part B:

“…if a beneficiary receives hospital outpatient services on the same day as a specimen collection and laboratory test, then the patient is considered to be a registered hospital outpatient and cannot be considered to be a non-patient on that day for purposes of the specimen collection and laboratory test. However, if the non-CAH or Maryland waiver hospital only collects or draws a specimen from the beneficiary and the beneficiary does not also receive hospital outpatient services on that day, the hospital may choose to register the beneficiary as an outpatient for the specimen collection or bill for these services as non-patient on the 14X bill type.“

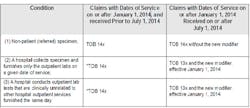

Today, this option of a hospital choosing how to categorize and bill these patients no longer exists. Under OPPS, the definitions have changed and are very clear. Outpatients lab services were added to those that receive bundled reimbursement effective January 1, 2014, and SE 1412 explicitly changed the type of bill (TOB) for specific patient types (Table 2).

CMS has made it clear that to properly bill, hospitals assign TOB 13X to all bills for outpatient hospital services and TOB 14X for non-patient (referred) laboratory specimens. A non-patient is defined as a beneficiary who is neither an inpatient nor an outpatient of a hospital, but has a specimen that is submitted for analysis to a hospital and is not physically present at the hospital. Importantly, and this represents a necessary review by all labs who previously may have optioned differently in the definition of their Outreach NPs, TOB 14X should only be billed for non-patient lab specimens. Only these claims, with few exceptions, are paid under the CLFS at the lesser of the actual charge, the fee schedule amount, or the National Limitation Amount (NLA, and the Part B deductible and coinsurance do not apply for laboratory tests payable on the CLFS.)

There are limited exceptions to the bundling requirement for Outpatient laboratory services. But where the exception exists, it would qualify the testing to be billed separately and paid under the CLFS. Some examples of exceptions, listed below, would append an L1 modifier on the TOB 13X which basically announces the exception to the bundling and payment via the CLFS:

- Outpatient lab tests only—Hospital only provides outpatient laboratory tests to the patient (directly or under arrangement) and the patient does not also receive other hospital outpatient services on that day.

- Unrelated outpatient lab tests—Hospital provides an outpatient laboratory test (directly or under arrangement) on the same date of service as other hospital outpatient services that is clinically unrelated to the other hospital outpatient services, meaning the laboratory test is ordered by a different practitioner than the practitioner who ordered the other hospital outpatient services, for a different diagnosis.

CMS notes that it is optional for a hospital to append the L1 modifier and seek separate payment under the CLFS. CMS is concerned that hospitals may adopt new scheduling patterns in order to circumvent the bundling requirement. Importantly, payment is bundled into a single payment regardless of whether the date of service spans multiple days. A lab does not have to use the L1 modifier. As an example, if you know that pre-op lab testing is taking place on a different date of service than the primary service, under the intent of the regulation it may be wise not to use the modifier as a means to collect more dollars and circumvent the bundling rule. To mitigate compliance risk, lab leaders should check with the hospital compliance and legal departments on the use of the L1 modifier for their facility and develop sound and consistent policies with staff highly trained in the designation of patient registration.

Patient reimbursement

In addition to new reimbursement models, the lab industry is faced with a growing portion of its revenue coming directly from the patients. Employers are pushing the rising costs of health insurance onto employees, creating a shift toward high-deductible health plans. The patients are experiencing increased out-of-pocket expenses. Bad debt and uncollectible balances are therefore increasing lab write-offs. One direction to consider is a retail model of having the tools and staff to collect a balance as able up front. Additionally, the billing department must have the knowledge and processes in place to help maximize the patient collections in a timely manner.

Strategies to remain viable

To survive in these new reimbursement models, labs must be proactive with a plan to stay ahead of the end of fee-for-service and maximize their outreach market. With inpatient procedures shrinking by single digits each year and outpatient procedures growing at double-digit rates annually, labs must have access to outpatient and outreach specimens.7

Labs should continue to look for opportunities to regionalize and consolidate to reduce cost per test and better position themselves to add value in an integrated care delivery system. They should go beyond result reporting to develop real-time analytics that deliver added value in the form of business and clinical intelligence that will support physicians and hospitals in the focus on population health management.

They should maximize their revenue cycle management and consider outsourcing the outreach billing to a lab-specific vendor for focused attention on collections. Labs should also review compliance and regulatory policies and update processes as needed. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued its 2015 Work Plan and identified a clinical laboratory project focused on the clinical laboratories submission of claims that are noncompliant with Medicare billing requirements; particularly duplicate testing and claims with ineligible or invalid ordering physician numbers. It would be beneficial for labs to proactively review claims and assess compliance with regard to the OIG report’s 13 measures of questionable billing. To view the actual report, go to: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-11-00730.pdf

Finally, lab management should consider engaging partners to help develop and implement solutions for further improvements that drive and sustain the fiscal viability of the laboratory during these reimbursement changes.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. [News release. 1.26.2015.] www.hhs.gov/news/press/2015pres/01/20150126a.html. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- American Medical Association. H-160.919 principles of the patient-centered medical home. https://www.ama-assn.org/ssl3/ecomm/PolicyFinderForm.pl?site=www.ama-assn.org&uri=/resources/html/PolicyFinder/policyfiles/HnE/H-160.919.HTM. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- American Association of Family Physicians. Patient-centered medical home. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/pcmh.html. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- Donaldson MS, Yordy KD Lohr, KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 1996.

- RAND Corporation. Analysis of bundled payment. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR562z20/analysis-of-bundled-payment.html. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Better care, smarter spending, healthier people: improving our health care delivery system. [Fact Sheet]. http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26.html. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. MedPac report to Congress: Medicare payment policy: 2015–. http://www.slideshare.net/devkambhampati/medpac-report-to-congress-2015-medicare-payment-policy. Accessed June 25, 2015.