Compliance with regulatory and accrediting agency requirements is dependent on the competency and willingness of transfusion service staff members to perform their duties as instructed. Management may be responsible for ensuring that immunohematology procedures are consistent with equipment and that reagent manufacturers’ instructions for use are in compliance with regulatory agency requirements and meet the individual facility’s requirements, but it is the transfusion service technologists who are critical: they are actually performing the tests. Over time, staff members may have introduced personal modifications to tasks in order to improve productivity or reduce costs. This has been termed “procedural drift.” This article will review how we have used competency assessments and other audits in our transfusion service at the University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers to verify that staff members are competent and performing their duties according to facility-defined procedures. The competency assessment tools described are most relevant for moderately complex and highly complex tests. The suggestions below represent the lessons learned from experiences in assessing employee competency.

Sponsored by Bio-RadTo earn CEUs, visit www.mlo-online.com/ce

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

- Understand the importance of efficiently assessing laboratory personnel competency during the first year of employment and beyond.

- Understand what procedural drift is and describe different ways to monitor it in the laboratory.

- Define the terminology associated with MSBOS.

- Understand the importance of MSBOS implementation in an institution.

- List and explain which surgical procedures would require T/S or T/C to be performed preoperatively.

Training and documentation

FDA regulations require that staff be trained to perform their duties. In addition, staff must receive training on the current good manufacturing practices regulations that apply to their role.1 Both regulations in the good manufacturing practices section of the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 211 and 21 CFR 600-640) and the regulations implementing the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) in 42 CFR 493 require trained staff. Documentation is the way to prove that staff is trained. In December 2012 CMS published CLIA Brochure 10, What Do I Need to Do to Assess Personnel Competency? in order to improve competency assessments in the field.2 That brochure outlines the requirements for competency assessment, including those individuals who may assess the competency of others.

Most facilities create a checklist of tasks for which new staff members will receive training. One lesson, learned the hard way, was the difficulty in keeping track of progress when there was one big 20-page checklist. Breaking up the checklist into sections and including in a separate section all of those tasks that are rarely performed together means that the majority of the documentation can be safely stored in the personnel file. In addition to the checklist, some accrediting agencies, such as the AABB, expect a training plan. However, this is not a CLIA requirement. The training plan defines the activities that are included in training, such as reading specific sections of the standard operating procedure, observing live demonstrations, watching videos or completing online learning courses, performing tests using previously tested specimens, quizzes, and any directed observations of performance. Training plans should be developed for training new employees, for training current employees when new tests are brought on line, and for employees who have returned to work after a month or more off the job.

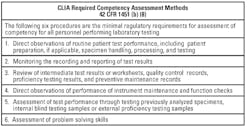

Once training has been completed, the staff member’s competency to perform laboratory testing must be documented using the six methods of competency assessment given in Table 1. The designers of the competency assessment requirements included the need to perform competency assessment twice during the first year of employment and annually thereafter.3 They recognized that the first year is critical in forming work habits and acquiring the knowledge to perform tasks. The additional competency assessment is necessary to identify areas for additional training or coaching.

Test methods and competency assessments

The six methods of competency assessment listed in Table 1 are required for laboratory testing, but not all tasks in the Transfusion Service are laboratory tests. Thawing plasma, dispensing a blood component, or ordering blood from the blood supplier, for example, are not test-related activities. Competency assessment is still expected, but these tasks do not require competency assessment using the six methods required under CLIA laboratory testing regulations.

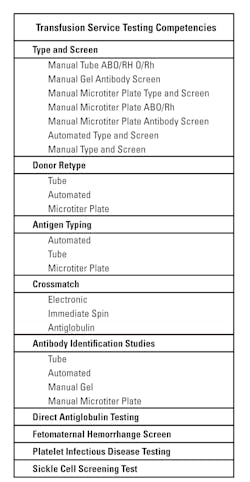

A well thought-out plan for competency assessment will reduce the amount of staff and supervisory time spent. Each method used defines a test “system” and constitutes the need for a competency assessment activity. When tests are done on an automated instrument and all of the testing has the same problems and there are no unique aspects, the competency assessments can be combined. The AABB indicated in a 2012 assessor’s workshop that, at a minimum, the assessor should expect to view documentation of competency assessment for the CLIA-regulated analytes: ABO, Rh, unexpected antibody detection, compatibility testing, and antibody identification. If those tests are performed by more than one technique in the laboratory, the staff members’ competency needs to be assessed using each method. Competency assessment cannot be eliminated because the method is the “backup method” and is used infrequently. One could argue, in fact, that if tests are rarely performed, they are the tests that need the most scrutiny. Clearly, the more methods used, the more competency assessments need to be performed. Table 2 lists tests and various methods that are used in Transfusion Services.

Once the number of competencies needed to be performed is defined, the next step is scheduling. Spreading tests out through the year makes sense. Waiting until December each year is probably not a good idea. It may be possible to group some tests together. Performing a transfusion reaction investigation may provide the opportunity for the supervisor to observe several tests at one time. It may be useful to create a competency that includes manual ABO, Rh, antibody screen, and a DAT. However, if transfusion reactions are infrequent, it may be more useful to find other test groupings that will provide more than one competency.

Equipment: maintenance and function checks

The requirement to observe staff performing maintenance and function checks applies for almost all testing in a transfusion service, even when the transfusion service does not have automated testing or when the maintenance is performed by another department or contracted to an outside agency. However, even an ABO/Rh test has equipment associated with the test. To determine competency for function checks, supervisors should ask open-ended questions during direct observation, such as “How do you know that the serological centrifuge is operating appropriately?” Staff members should be able to access the records of maintenance and function checks and answer questions about the frequency of testing or whether the instrument has been maintained according to the requirements of the procedure. Another benefit is the potential for incidental findings such as equipment overdue for maintenance or periodic quality control testing.

Designing the assessment tool

The assessment tool should include the following information:

- employee identification

- date of the review

- description of the competency being reviewed

- checklist of critical steps that must be performed

- technical details, such as the number of drops of reagent and patient cells, plasma or serum, incubation time, and centrifuge/instrument settings

- recording and evaluating test result, and finally

- reporting results.

Supervisors should include review of quality control records and questions that assess the staff member’s problem-solving skills. They should ask more open-ended questions such as “What types of specimens cannot be used for this test?’ or “What would you do if ______ occurs”? and avoid ambiguous questions that may cause staff to fail. The tool can be validated by performing a mock assessment.

Also, supervisors should define what is to be done if the staff member fails the competency assessment. Should he or she perform testing under the direct supervisor until a repeat competency assessment has been passed? Or is there some other action related to the competency failure that will allow the staff member to become competent? Reading the procedure manual in itself is not an effective remedial response for a person who had failed a competency on antibody screening. As indicated before, supervisors should avoid putting all of the competencies on one huge form, but rather divide them into reasonable packets. A tally sheet with the names of the employees on one axis and the names of the competencies on the other could be used. An alternative method of recordkeeping is a competency summary sheet for each employee that uses one axis for each of the six methods and the other axis with the competencies to be done. The supervisor can enter the date, specimen identification, and pass/fail result for each competency on the form.

Who can perform competency assessment?

All individuals who participate in laboratory testing need to have their competency assessed. If a supervisor performs testing, then his or her competency needs to be assessed. The person doing the competency assessment does not need to be classified as a supervisor, but he or she must meet the CLIA requirements of a general supervisor for that specialty area.4 The CLIA regulations for general supervisor can be found in 42 CFR 493.1461.

Whose rules are these anyway?

Medical laboratory science training programs focus on the science of performing laboratory testing and spend less time teaching standards and regulations. Although there is usually a course in laboratory management, out of necessity it is an overview of many regulatory topics ranging from safety to personnel management, with a sprinkling of information about laboratory regulatory and accrediting agencies.

Supervisors are very aware of their accrediting agency requirements such as the AABB, ASHI, CAP, Joint Commission, and COLA, among others. However, they may not be familiar with the Code of Federal Regulations, and they may fail to recognize that many of the requirements of accrediting agencies are included because of requirements in either the 21 CFR 211 and 21 CFR 600-640 sections related to blood establishments or the 42 CFR 493 CLIA regulations for laboratory testing.

There are several ways for supervisors to ensure that staff members are aware of and can apply the regulations in doing their daily work. From the first week the new employee is in the laboratory, regulatory compliance can be included in training activities. Regulatory citations must be included in the reference section of the standard operating procedures manual. Trainers can include exercises that require trainees to look up and read the Code of Federal Regulations and the standard of the accrediting agency used by the organization. For example, proficiency testing procedures should reference the CLIA regulations, and a question during training might include a discussion of the CLIA requirement that each technologist who performs a specific test such as ABO and Rh typing perform reagent quality control testing periodically. Or, the staff member could be asked why quality control tasks are rotated among all staff members.5

Asking the trainee to read the regulations may seem like an unnecessary task, as the primary goal is to get the person performing routine work as quickly as possible. But there really is no better time to train a technologist to recognize that there is a federal regulation that requires rotation of daily reagent quality control, or that there is a regulation requiring that, when placing supplies that do not have an outdate printed on the box or package, the supplies need to be stored so that the oldest is used first.6 That is always a good laboratory practice, but how many staff technologists know it is a regulation?

Following the manufacturer’s instructions

In general, the manufacturer’s instructions are to be followed when performing testing. It does not matter whether the test is waived, of moderate complexity, or of high complexity. When a facility determines that modifications to the manufacturer’s instructions are warranted, the modified test process must be fully validated before being implemented. In the transfusion service as well as in the clinical laboratory in general, there is an emphasis on involving staff members in process design and process improvement. The technologist who is unaware of the requirement to follow the manufacturer’s instructions may decide to test an innovation without analyzing the risks involved in making the modification and validating the revised process. The goal may be to save set-up time, to save effort by making the process “lean,” or to reduce turnaround time. These goals may be well intentioned but fail to meet regulatory requirements.

And, staff tend to receive training about the need to follow the manufacturer’s instructions for a test most readily—when they are learning to perform the test. A review during training of the product or kit instructions for use, the operator’s manual for equipment, and the lab’s procedure provides an opportunity to discuss how regulations and manufacturer’s instructions for use of reagents and equipment are reviewed and stored for reference and how changes are made to the SOPs. The importance of lot number control and the process for changing lot numbers are also critical topics to be discussed during the training period.

Competency assessment at the end of training provides opportunities to determine whether staff can apply the principles of good manufacturing practices to problem-solving scenarios and case studies. A scenario that includes the need to review the manufacturer’s instructions should be included in the competency assessment. While a staff technologist is not likely to be the person who files a biological product deviation report with the FDA, he or she needs to be able to identify a potential reportable error and document the circumstances surrounding the occurrence.

Another method of detecting procedural drift is to audit test performance and documentation. This differs from competency assessment in that the person performing the task is not being graded. With the assistance of the section supervisor, our auditor prepares a checklist of critical steps in a process and lists those on the audit form. In addition, they create a list of three or four questions that focus on topics such as lot number control, actions to be taken if the QC on the automated instrument fails, or the age of the specimen that can be used for testing. There are a myriad of potential questions that can be asked. We have included processing errors that have resulted in biological deviations that needed to be reported to the FDA as well as requests for information that can only be found in the product instructions for use.

Auditors introduce themselves to the staff member and indicate they are doing an audit. They explain that the goal is to understand how the individual performs a specific task. The staff member is given open-ended instructions such as “Show me how you do this test” or “Tell me what you do when X happens,” or asked open-ended questions such as “Have you made any improvements to the process that makes it more efficient?” Asking this last question has resulted in identifying personal “time-saving process improvements” that may, in fact, defeat the safety mechanisms built into the approved process. In some cases, staff members will admit that they do not follow the procedure because they “like” two drops of reagent rather than one when performing testing using anti-D reagents because “it works better for me.”

Procedural drift can also be detected when investigating errors. For example, before we had software that would detect whether two blood types were performed and verified, several staff members decided that it was simpler to determine if a repeat blood type was completed by observing the notation “RPTBT” on the paper requisition. This meant that a previous individual identified the patient as needing a second blood type. Unfortunately, the test may never have been ordered at all, or ordered and not completed. The only way to verify that two types had been ordered and verified was to follow the procedure and look up the results in the computer. While well intentioned, the modified process led to FDA reportable errors when units of red blood cells were issued and the second type was not completed, and an electronic rather than a serologic crossmatch had been used to determine compatibility.

Another successful competency assessment tool that can identify deviations from standard procedures is asking staff members to submit an antibody workup they have performed so that their problem-solving skills can be assessed. The review is based on a checklist with specific predefined criteria. Have they performed testing and evaluated the results according to the facility’s procedures? Were there deviations from the reagent manufacturer’s instructions? Was appropriate quality control testing documented? Was the conclusion appropriate? Just as deviating from the method of determining if two blood types are on file can lead to reportable errors and potential patient harm, not following the rules for making antibody exclusions can lead to incorrect antibody identification and the potential for an incompatible transfusion.

We have also used competency assessment case studies with reactions already recorded on our antibody panel sheets. We ask staff what antibodies are most likely, what antibodies have not been ruled out using our rule out criteria, and what the next steps are. These can be presented as a combination of short answer and multiple choice questions. Some years, we have assessed tube reading by providing the same wet unknown specimen to all staff. This requires excellent planning, as changes in reagent lot numbers make test result variances difficult to interpret. We expect the staff member to call a negative test negative. However, we do not expect that each technologist will grade the positive reaction the same strength. That being said, if one individual recorded results as +/- positive when everyone else graded the reaction as 4+, that would be cause to investigate the possible cause of the discrepancy.

So in summary…

When staff members are not aware of the regulations that govern laboratory testing, they are more likely to make well-intended but unfortunate decisions when performing their daily activities. In transfusion service facilities, there sometimes is a pervasive attitude that compliance is the sole responsibility of the supervisor, and staff members do not need to know the regulations. I disagree wholeheartedly. A staff member’s decision to report patient results even though the instrument was unable to read the quality control reactions, requiring a manual interpretation and modification of results, or a decision to make seemingly slight modifications in a validated process, or to take short cuts to improve efficiency, can affect the safety, reliability, and accuracy of a test result. In becoming efficient, staff members may fail to comply with the manufacturer’s instructions for performing the test and compromise the test results and patient care. The challenge for a supervisor in the Transfusion Service is to encourage suggestions for process improvement while managing the change so that revised procedures are assessed for risk to the patient, and are validated, documented, and evaluated after the change to determine if they resulted in the positive impact without causing any unforeseen and negative consequences.

Competency assessment provides the supervisor with opportunities to verify staff competency and identify testing modifications that may cause patient harm and FDA reportable errors. Staff training in regulatory compliance is essential and should be incorporated into routine training. Audits of adherence to the manufacturer’s instructions provide an additional method of identifying ad hoc procedure modifications and procedural drift.

References

- US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, Code of Federal Regulations. Standard: Personnel Qualifications. 21 CFR 211.25.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Department of Health & Human Services. What Do I Need to Do to Assess Personnel Competency? CLIA Brochure 10.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Department of Health & Human Services, Code of Federal Regulations. Standard: Technical Supervisor Responsibilities. 42 CFR 1451 (b) (8).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, Code of Federal Regulations. Standard: General Supervisor Qualifications. 42 CFR 493.1461.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, Code of Federal Regulations. Standard: Control procedures. 42 CFR 493.1256 (d) (7).

- US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, Code of Federal Regulations. Standard: Supplies and Reagents. 21 CFR 606.65 (d).