In April of this year, the microbiology techs at the MidMichigan Medical Center in Midland, MI, were exposed to a living culture of Brucella species, a biosafety level3 (BSL-3) pathogen. Since our laboratory is classified and operates according to biological safety level 2 (BSL-2) guidelines, our exposure was a rare and unfortunate occurrence. Because Brucella ssp is listed as one of the biological agents that could be used for bioterrorism, the local and state Bioterrorism Response Network was also activated.Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria of the genus

Brucella. Primarily passed among animals, these bacteria cause disease in many different vertebrates. Currently, of the six main species of Brucella, four have moderate-to-significant pathogenicity for humans:Brucella suis (from pigs; high pathogenicity);Brucella melitensis (from sheep; highest pathogenicity);Brucella abortus (from cattle; moderate pathogenicity); andBrucella canis (from dogs; moderate pathogenicity).

Brucella. Primarily passed among animals, these bacteria cause disease in many different vertebrates. Currently, of the six main species of Brucella, four have moderate-to-significant pathogenicity for humans:Brucella suis (from pigs; high pathogenicity);Brucella melitensis (from sheep; highest pathogenicity);Brucella abortus (from cattle; moderate pathogenicity); andBrucella canis (from dogs; moderate pathogenicity).

Brucellosis is not common in the United States, where 100 to 200 cases occur each year.1 In countries where animal disease-control programs have not reduced the amount of disease among animals, brucellosis can be very common. Humans become infected by coming into contact with animals or animal products, such as unpasteurized dairy products, that are contaminated with these bacteria. Unpasteurized cheeses, sometimes called village cheeses, from endemic areas like the Mediterranean Basin Portugal, Spain, Southern France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, North Africa may represent a particular risk for tourists. The incubation period is highly variable, but symptoms usually appear within five to 30 days.In humans, brucellosis can cause a range of symptoms that are similar to the flu and may include fever, sweats, headaches, back pains and physical weakness. Brucellosis can also cause long-lasting or chronic symptoms that include recurrent fevers, joint pain and fatigue. It can be misdiagnosed as chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia syndrome, but it is rarely fatal.2 Generally, it is not transmitted from person to person.MidMichigan Medical case study

On April 2, a 32-year-old gentleman presented to MidMichigan Medicals emergency room (ER) for fever of undetermined origin. He was a Mexican native who had been visiting Mexico in December 2002. During that time, he stayed at his familys dairy farm where he consumed unpasteurized milk. While in Mexico, he had sustained a gastrointestinal illness. Although he had been prescribed three medications at the pharmacy there, he did not recall what they were. He did state that he felt better after taking them. After returning to the States in January 2003, he started feeling generalized malaise, weakness, profuse sweating, intermittent low-grade fevers and a 20-pound weight loss. His health had finally deteriorated to the point where he could not work.Two sets of blood cultures and a complete blood count were drawn from the patient at the time of his admission to the ER. The CBC was essentially normal with no leukocytosis. The patient was discharged from the ER on the same day, but was asked to return on April 6 after the blood cultures were reported positive for tiny, faintly staining, gram-negative coccobacilli. The patient was admitted to the medical floor and started on ampicillin and gentamicin. On April9, the positive blood cultures were identified as presumptive

Brucella ssp, which prompted discontinuation of the initial antibiotic regimen in favor of a six-week course of rifampin plus

doxycycline.Lab biosafety levels: a Catch-22Brucellosis continues to be the most commonly reported laboratory-acquired bacterial infection. Cases have occurred in the clinical laboratory setting from aerosols generated during laboratory procedures and sniffing bacteriological cultures. The human infectious dose of

Brucella ssp can be as low as 10 organisms by the respiratory route (see

Table 1, see below).Table 1: Some

common biological warfare agents that can be used for bioterrorismLethal

AgentsDisease

or agentLethality

(death)Incubation periodEffective doseEnvironmental

stabilityAnthraxHigh1 to 6 days10,000 to 50,000 sporesVery

stable for yearsPlagueHigh1 to 6 days100 to 500 organismsStable

for one yearSmallpoxHigh7 to 17 days10 to 100 organismsVery

stableEbola

virusHigh2 to 6 days10 to 100 organismsUnstableBotulismHigh2 to 6 days0.001 mcg/Kg weightRelatively

stableRicinHigh1 to 5 days3 to 5 mcg/Kg weightStableCholeraHigh1 to 3 days10 to 500 organismsUnstableIncapacitating

agentsBrucellosisLowMonths10 to 100 organismsVery

stableTularemiaLow2 to 15 days10 to 50 organismsStable

for monthsQ

FeverLow15 to 40 days1 to 10 organismsStable

for monthsMycoplasmaLowMonths10 to 100 organismsModerately

stableT-2

MycotoxinsLowOne dayUnknownVery

stableType

B EnteroxinModerate0.03 mcgModerately

stableEquine

encephalitisLow2 to 6 days10 to 100 organismsUnstableReference:

Emergency Responder Disaster Management 2001BSL-2 practices are recommended for handling human specimens that may contain

Brucella ssp. Infections may occur when laboratory workers do not expect this pathogen and neglect to take appropriate safety measures. Biochemical misidentification of a Brucella species as a Moraxella species, with the consequent mishandling, has been shown to be a reason for laboratory-acquired brucellosis.3 Clinical specimens that could contain this agent include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), semen, urine and blood. Microbiologists should wear gloves at all times when handling potential isolates of this agent.The BSL-2 standard, however, applies

only at the time of exposure to potentially infectious material. Once the culture plates have grown, there is no requirement that the culture work-up be performed in the safety cabinet. Therefore, BSL-2 laboratories are at risk, albeit rarely, for exposure to level3 pathogens before they have been presumptively identified.BSL-3 facilities do require that all manipulations of suspected or confirmed

cultures of Brucella ssp considered at this stage to be a BSL-3 organism requiring a heightened level of concern for the clinical microbiology laboratory be performed in the biosafety cabinet. This is especially urgent with activities that might create an aerosol. Infection has been more commonly associated with cultures than with clinical materials. Laboratories should immediately assume an enhanced level of biosafety (gown, gloves, biological safety cabinet) in dealing with suspect or confirmed isolates of this organism. Direct contact of skin or mucous membranes with cultures, and accidental parenteral inoculations have also resulted in infection.Identifying Brucella

Brucella ssp, which prompted discontinuation of the initial antibiotic regimen in favor of a six-week course of rifampin plus

doxycycline.Lab biosafety levels: a Catch-22Brucellosis continues to be the most commonly reported laboratory-acquired bacterial infection. Cases have occurred in the clinical laboratory setting from aerosols generated during laboratory procedures and sniffing bacteriological cultures. The human infectious dose of

Brucella ssp can be as low as 10 organisms by the respiratory route (see

Table 1, see below).Table 1: Some

common biological warfare agents that can be used for bioterrorismLethal

AgentsDisease

or agentLethality

(death)Incubation periodEffective doseEnvironmental

stabilityAnthraxHigh1 to 6 days10,000 to 50,000 sporesVery

stable for yearsPlagueHigh1 to 6 days100 to 500 organismsStable

for one yearSmallpoxHigh7 to 17 days10 to 100 organismsVery

stableEbola

virusHigh2 to 6 days10 to 100 organismsUnstableBotulismHigh2 to 6 days0.001 mcg/Kg weightRelatively

stableRicinHigh1 to 5 days3 to 5 mcg/Kg weightStableCholeraHigh1 to 3 days10 to 500 organismsUnstableIncapacitating

agentsBrucellosisLowMonths10 to 100 organismsVery

stableTularemiaLow2 to 15 days10 to 50 organismsStable

for monthsQ

FeverLow15 to 40 days1 to 10 organismsStable

for monthsMycoplasmaLowMonths10 to 100 organismsModerately

stableT-2

MycotoxinsLowOne dayUnknownVery

stableType

B EnteroxinModerate0.03 mcgModerately

stableEquine

encephalitisLow2 to 6 days10 to 100 organismsUnstableReference:

Emergency Responder Disaster Management 2001BSL-2 practices are recommended for handling human specimens that may contain

Brucella ssp. Infections may occur when laboratory workers do not expect this pathogen and neglect to take appropriate safety measures. Biochemical misidentification of a Brucella species as a Moraxella species, with the consequent mishandling, has been shown to be a reason for laboratory-acquired brucellosis.3 Clinical specimens that could contain this agent include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), semen, urine and blood. Microbiologists should wear gloves at all times when handling potential isolates of this agent.The BSL-2 standard, however, applies

only at the time of exposure to potentially infectious material. Once the culture plates have grown, there is no requirement that the culture work-up be performed in the safety cabinet. Therefore, BSL-2 laboratories are at risk, albeit rarely, for exposure to level3 pathogens before they have been presumptively identified.BSL-3 facilities do require that all manipulations of suspected or confirmed

cultures of Brucella ssp considered at this stage to be a BSL-3 organism requiring a heightened level of concern for the clinical microbiology laboratory be performed in the biosafety cabinet. This is especially urgent with activities that might create an aerosol. Infection has been more commonly associated with cultures than with clinical materials. Laboratories should immediately assume an enhanced level of biosafety (gown, gloves, biological safety cabinet) in dealing with suspect or confirmed isolates of this organism. Direct contact of skin or mucous membranes with cultures, and accidental parenteral inoculations have also resulted in infection.Identifying Brucella

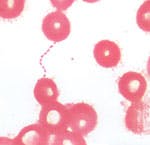

Our hospital-based laboratory is a BSL-2 facility. From the two sets of blood cultures drawn from this ER patient on April 2 (10 mL of blood delivered into an aerobic blood culture bottle and 10 mL into an anaerobic bottle per set), all four bottles were placed in our automated blood culture instrument (we use a bioMerieux BacTAlert). After four days incubation, both aerobic bottles were flagged as positive. In accordance with laboratory BSL-2 practices, all unpreserved clinical materials must be handled,4 as well as certain procedures in which infectious aerosols or splashes might be created conducted, in a biological safety cabinet or other physical containment. The bottles from our patient were placed in the biological safety cabinet where blood smears were prepared.After the smears had dried in the safety cabinet, they were methanol fixed and Gram stained. We saw very faintly staining, tiny gram-negative coccobacilli in clusters and chains. Because the organisms appeared to be unusually small, we made a wet-prep from the culture broth and performed a darkfield examination.5 Under darkfield, the organisms were much easier to define and looked like nonmotile coccobacilli, resembling bicycle chains. We subcultured each positive aerobic bottle to blood agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar and CDC anaerobic blood agar. After two days incubation at 35C 7%CO2, very tiny colonies appeared on the blood and chocolate agar plates. No growth appeared on the MacConkey plate or anaerobic CDC blood agar plate. Gram stain showed tiny faintly staining gram-negative

coccobacilli.Exposure to a BSL-3 pathogen, such as

Brucella ssp is an uncommon occurrence for a BSL-2 clinical laboratory in the United States. Special precautions should always be taken when tiny, faintly staining, gram-negative coccobacilli are seen on direct Gram stain of clinical material (e.g., CSF, bone marrow, blood cultures, semen). All subcultures should be performed in the biological safety cabinet and media plates should be sealed in biohazard bags and isolated from other culture plates in the incubator. Bags should be opened and manipulated only in the biological safety cabinet until suspicion of a level3 pathogen has been ruled out.Our microbiology tech performed a catalase test (strongly positive), a rapid urease test (strongly positive), an oxidase test (positive) and Gram smear from colony growth. When a presumptive identification of

Brucella ssp was made, all culture media was immediately sealed in biosafety bags and all further work-up was performed in the biological safety cabinet.6 (The infected patients initial

Brucella serum microagglutination titer was 1:1280, the results of which were not available to us until one week after isolation of the organism.)In addition, to minimize risk to personnel receiving the culture, all isolates suspected of being

Brucella spp must be immediately packaged and shipped for confirmation to the state health department as

dangerous goods per the guidelines established by the World Health Organization and the Office of Biosafety at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).7 When our preliminary identification was made, for example, we immediately called our state health department to warn officials that a presumptive

Brucella ssp culture was in transit to their facility.A close to the Brucella exposureOur state health department forwarded our

Brucella isolate to the CDC in Atlanta where it was subsequently identified as

Brucella melitensis. Three of our MidMichigan microbiology techs were exposed to the living culture and, consequently, were placed on prophylactic doxycycline plus rifampin for six weeks.8 Because of intolerant side effects of the rifampin, one tech had to discontinue this antibiotic before the six-week regimen was up. Acute and convalescent serology titers for

Brucella were negative for all three techs. Because of its nonspecific symptoms and insidious onset, brucellosis is often difficult to diagnose. It is also rare in the United States and may not be suspected by ordering physicians; therefore, the microbiology laboratory plays a pivotal role in the recognition of this disease, and may be the first point at which an outbreak or bioterrorism event will be recognized.ReferencesCDC Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Disease. Brucellosis. June. 2001.Co-Infections in Fibromyalgia Syndrome, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome & Other Chronic Illness. In:

Fibromyalgia Frontiers, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2002:5-9, 27-28.Batchelor BI, Brindle RJ, Gilks GF, Selkon JB. Biochemical misidentification of Brucella melitensis and subsequent laboratory-acquired infections.J Hosp Infect. 1992; 22:159-162.US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Institutes of Health.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 4th ed. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC; 1999.Davidson M, Abramowitz M.

Darkfield Illumination in Molecular Expressions 1998-2003. Olympus America Inc., and Florida State University; 1999.Shapiro DS, Wong JD.

Brucella. In Murray PR, Barron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH, eds.

Manual of Clinical Microbiology 7th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1999:625-631.Transport of Infectious Substances. In:

Laboratory Biosafety Manual 2nd ed. (revised). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003:Chapter 12.Brucellosis. In:

Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease. 5th ed., 2000:353-354.CDC. Biological and chemical terrorism: strategic plan for preparedness and response: recommendations of the CDC Strategic Planning

Workgroup. Publication MMWR 2000:49 (No. RR-4).Regis E. The Biology of Doom: The history of Americas secret germ warfare

project. Henry Holt and Co.; 1999.Biological weapons: malignant biologyBrucella ssp and bioterrorismThe main function of bioterrorism is to cause panic, disruption and chaos, so biological agents do not have to cause a fatal disease to be effective.9 In fact, many biological warfare agents categorized as incapacitating agents are not intended to produce fatal disease (e.g.,

Brucella ssp). They are more effective if they incapacitate and produce strain on a healthcare system by having many thousands of sick patients inundate treatment facilities.Brucellosis can cause tremendous chronic health problems in infected patients. The disease develops slowly over several months as a flu-like infection with nonspecific signs and symptoms, including intermittent fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, muscle pain and soreness, cough and eventually joint pain and soreness, gastrointestinal complaints, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and constipation.Given the ease of aerosol transmission, researchers attempted to develop

Brucella spp into a biological weapon in 1942. In 1954, it became the first agent weaponized by the old U.S. offensive biological weapons program. By 1955, the United States was producing

Brucella suis-filled cluster bombs for the U.S. Air Force at the Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas.Development of brucellae as a weapon was halted in 1967, and then-President Nixon later banned development of all biological weapons on November 25, 1969. Although the

Brucella munitions never were used against human targets, the research performed resulted in concern that

Brucella species someday might be used as a weapon against either military or civilian objectives.10For 15 years, Colleen Gannon, MT(AMT), HEW, has been the section head of the microbiology department of MidMichigan Medical Center, which services the 308-bed nonprofit hospital, in addition to two other area hospitals, several nursing homes, satellite laboratories and clinics.

September 2003: Vol. 35, No. 9© 2003 Nelson Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved.

coccobacilli.Exposure to a BSL-3 pathogen, such as

Brucella ssp is an uncommon occurrence for a BSL-2 clinical laboratory in the United States. Special precautions should always be taken when tiny, faintly staining, gram-negative coccobacilli are seen on direct Gram stain of clinical material (e.g., CSF, bone marrow, blood cultures, semen). All subcultures should be performed in the biological safety cabinet and media plates should be sealed in biohazard bags and isolated from other culture plates in the incubator. Bags should be opened and manipulated only in the biological safety cabinet until suspicion of a level3 pathogen has been ruled out.Our microbiology tech performed a catalase test (strongly positive), a rapid urease test (strongly positive), an oxidase test (positive) and Gram smear from colony growth. When a presumptive identification of

Brucella ssp was made, all culture media was immediately sealed in biosafety bags and all further work-up was performed in the biological safety cabinet.6 (The infected patients initial

Brucella serum microagglutination titer was 1:1280, the results of which were not available to us until one week after isolation of the organism.)In addition, to minimize risk to personnel receiving the culture, all isolates suspected of being

Brucella spp must be immediately packaged and shipped for confirmation to the state health department as

dangerous goods per the guidelines established by the World Health Organization and the Office of Biosafety at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).7 When our preliminary identification was made, for example, we immediately called our state health department to warn officials that a presumptive

Brucella ssp culture was in transit to their facility.A close to the Brucella exposureOur state health department forwarded our

Brucella isolate to the CDC in Atlanta where it was subsequently identified as

Brucella melitensis. Three of our MidMichigan microbiology techs were exposed to the living culture and, consequently, were placed on prophylactic doxycycline plus rifampin for six weeks.8 Because of intolerant side effects of the rifampin, one tech had to discontinue this antibiotic before the six-week regimen was up. Acute and convalescent serology titers for

Brucella were negative for all three techs. Because of its nonspecific symptoms and insidious onset, brucellosis is often difficult to diagnose. It is also rare in the United States and may not be suspected by ordering physicians; therefore, the microbiology laboratory plays a pivotal role in the recognition of this disease, and may be the first point at which an outbreak or bioterrorism event will be recognized.ReferencesCDC Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Disease. Brucellosis. June. 2001.Co-Infections in Fibromyalgia Syndrome, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome & Other Chronic Illness. In:

Fibromyalgia Frontiers, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2002:5-9, 27-28.Batchelor BI, Brindle RJ, Gilks GF, Selkon JB. Biochemical misidentification of Brucella melitensis and subsequent laboratory-acquired infections.J Hosp Infect. 1992; 22:159-162.US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Institutes of Health.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 4th ed. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC; 1999.Davidson M, Abramowitz M.

Darkfield Illumination in Molecular Expressions 1998-2003. Olympus America Inc., and Florida State University; 1999.Shapiro DS, Wong JD.

Brucella. In Murray PR, Barron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH, eds.

Manual of Clinical Microbiology 7th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1999:625-631.Transport of Infectious Substances. In:

Laboratory Biosafety Manual 2nd ed. (revised). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003:Chapter 12.Brucellosis. In:

Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease. 5th ed., 2000:353-354.CDC. Biological and chemical terrorism: strategic plan for preparedness and response: recommendations of the CDC Strategic Planning

Workgroup. Publication MMWR 2000:49 (No. RR-4).Regis E. The Biology of Doom: The history of Americas secret germ warfare

project. Henry Holt and Co.; 1999.Biological weapons: malignant biologyBrucella ssp and bioterrorismThe main function of bioterrorism is to cause panic, disruption and chaos, so biological agents do not have to cause a fatal disease to be effective.9 In fact, many biological warfare agents categorized as incapacitating agents are not intended to produce fatal disease (e.g.,

Brucella ssp). They are more effective if they incapacitate and produce strain on a healthcare system by having many thousands of sick patients inundate treatment facilities.Brucellosis can cause tremendous chronic health problems in infected patients. The disease develops slowly over several months as a flu-like infection with nonspecific signs and symptoms, including intermittent fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, muscle pain and soreness, cough and eventually joint pain and soreness, gastrointestinal complaints, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and constipation.Given the ease of aerosol transmission, researchers attempted to develop

Brucella spp into a biological weapon in 1942. In 1954, it became the first agent weaponized by the old U.S. offensive biological weapons program. By 1955, the United States was producing

Brucella suis-filled cluster bombs for the U.S. Air Force at the Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas.Development of brucellae as a weapon was halted in 1967, and then-President Nixon later banned development of all biological weapons on November 25, 1969. Although the

Brucella munitions never were used against human targets, the research performed resulted in concern that

Brucella species someday might be used as a weapon against either military or civilian objectives.10For 15 years, Colleen Gannon, MT(AMT), HEW, has been the section head of the microbiology department of MidMichigan Medical Center, which services the 308-bed nonprofit hospital, in addition to two other area hospitals, several nursing homes, satellite laboratories and clinics.

September 2003: Vol. 35, No. 9© 2003 Nelson Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Sign up for our eNewsletters

Get the latest news and updates