The FDA reviews guidelines for capillary glucose testing in critically ill patients

Capillary whole blood testing with point-of-care (POC) glucose meters in hospitalized patients and, particularly, in critically ill patients, remains a topic of interest in the medical and regulatory communities. However, determining the requirements for effective clinical use has proved challenging.

An FDA panel convenes

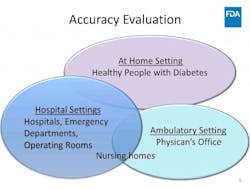

This past March, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) convened its Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Advisory Panel, seeking guidance and recommendations on the acceptability of capillary specimens in critically ill patients based on benefits and risks, and whether capillary specimen testing in this patient population meets the criteria for waived status under the Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments (CLIA) regulations.1

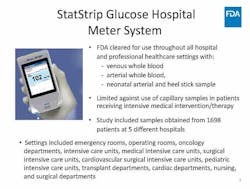

The FDA began by summarizing the history of POC glucose testing for the panel and emphasized the need for manufacturers to submit data supporting their glucose meters’ acceptability for use with critically ill patients. The FDA reviewed the data submitted for a glucose meter cleared for use with these patients using arterial and venous specimens,2 and related that no manufacturer had submitted data for capillary whole blood.

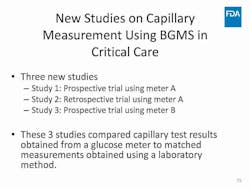

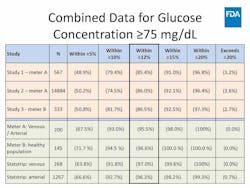

The panel was then presented with data from three large studies that compared capillary whole blood glucose to arterial and venous glucose in critically ill patients. Conducted by unidentified manufacturers, the studies used two different glucose meters that were compared to central laboratory results. The cleared glucose meter’s critical care claim data for arterial and venous testing was used as the benchmark for comparison.

The panel considers

Capillary performance was shown to be accurate, though less so than the other specimen types. The decrease in accuracy of capillary results surprised a number of panelists, including those specializing in critical care, who said that education was needed for clinicians and nurses regarding the difference in specimen performance.

The panel discussed at length both the analytical performance needs and the clinical factors that should be considered when determining whether capillary testing with a glucose meter is appropriate for critically ill patients, acknowledging that certain patient conditions may be more likely to produce questionable capillary results.

The inaccuracy of capillary glucose compared to arterial or venous glucose in certain conditions is due to inherent differences in the specimen types based on the physiology of capillary vessels and microcirculation. Capillary vessel networks diffuse glucose into surrounding fluid and tissue. The rate of diffusion is dependent on the rate of blood flow. Conditions such as hypoxia, hypotension, and hypoperfusion can cause capillary restriction, which reduces blood flow. When this happens, glucose diffuses more quickly and, as a result, capillary whole blood tested with glucose meters can produce elevated glucose readings compared to arterial or venous specimens.

The panel noted that in certain conditions, an unreliable capillary glucose reading could lead to misdiagnosing a patient and result in harm or death. However, a clear advantage of capillary testing is that the clinician receives immediate results. If the result does not agree with the patient’s clinical presentation, an arterial or venous specimen can be drawn and measured at the bedside, provided the POC meter is FDA-cleared for use with critically ill patients.2 This avoids the need for an alternative testing method yet ensures rapid results for faster clinical decision making and treatment.

The panel concludes

Ultimately, the panel decided that the use of capillary whole blood can be safe and effective for use with critically ill patients, despite the risk of inaccurate results associated with certain patient conditions or treatments. However, the panel did not reach consensus on how to determine which patients are eligible for capillary testing, due in large part to the lack of data and subjectivity regarding clinicians’ comfort levels in making this decision.

On the topic of CLIA waivers, the panel also had trouble reaching consensus. Several panelists argued for user-proficiency testing as a consideration in granting CLIA-waived status for capillary testing with glucose meters, which would prove testing to be simple and have “an insignificant risk of an erroneous result” for untrained users. Other panelists felt that special controls were needed to issue a CLIA waiver for glucose meters using capillary specimens with critically ill patients, advocating for a moderate-complexity status. However, panelists noted that unnecessary burden should not be placed on healthcare providers and acknowledged that capillary testing is currently integrated into hospitals and other clinical settings.

One glucose meter has CLIA waived status, which it received in 2007 as a result of its accuracy validation having been performed on hospitalized patients by the manufacturer. Other glucose meter manufacturers performed accuracy validation for their meters through an over-the-counter (OTC) pathway on generally healthy, non-hospitalized patients. As it stands today, and reinforced by the panel discussion, the OTC pathway for waived clearance is no longer an option, and manufacturers must validate meter performance with waived users and each intended use patient population. Otherwise, hospitals must perform this extensive validation themselves, or create alternative testing processes with other devices that are CLIA waived for the intended use patient population.

Following a day of discussion and deliberation, the panel reached consensus that because of the strong need for rapid, POC capillary testing with glucose meters in critically ill patients, along with the meters’ current widespread level of use, the benefits of capillary testing outweigh the potential risks. Even with the difference in performance of capillary versus arterial or venous whole blood specimens, the panel concluded that capillary testing can be safe and effective in this patient population if performed with a meter that has been cleared by the FDA to be safe and effective for use with critically ill patients.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA executive summary. 2018 Meeting Materials of the Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Panel. 30 March 2018.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Blood glucose monitoring test systems for prescription point-of-care use. 2016. Silver Spring, MD, FDA.

* FDA graphics source: Landree L. Measuring blood glucose using capillary blood with blood glucose meters in all hospital settings. Presented at the meeting of the Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Panel, Gaithersburg, MD: 30 Mar 2018.

About the Author