Two types of blood pressure meds prevent heart events equally, but side effects differ

People who are just beginning treatment for high blood pressure can benefit equally from two different classes of medicine – angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) – yet ARBs may be less likely to cause medication side effects, according to an analysis of real-world data published today in Hypertension, an American Heart Association journal.

While the class of blood pressure-lowering medicines called angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may be prescribed more commonly, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) work just as well and may cause fewer side effects. Currently, ACE inhibitors are prescribed more commonly than ARBs as a first-time blood pressure control medicine.

The findings are based on an analysis of eight electronic health record and insurance claim databases in the United States, Germany and South Korea that include almost 3 million patients taking a high blood pressure medication for the first time with no history of heart disease or stroke.

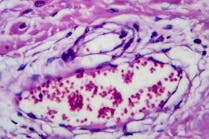

Both types of medicines work on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, a group of related hormones that act together to regulate blood pressure. ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure by blocking an enzyme early in the system so that less angiotensin, a chemical that narrows blood vessels, is produced, and blood vessels can remain wider and more relaxed. ARBs block receptors in the blood vessels that angiotensin attaches to, diminishing its vessel-constricting effect.

Health records for patients who began first-time blood pressure-lowering treatment with a single medicine between 1996-2018 were reviewed for this study. Researchers compared the occurrence of heart-related events and stroke among 2,297,881 patients treated with ACE inhibitors to those of 673,938 patients treated with ARBs. Heart-related events include heart attack, heart failure or stroke, or a combination of any of these events or sudden cardiac death recorded in the database. The researchers also compared the occurrence of 51 different side effects between the two groups. Follow-up times varied in the database records, but they ranged from about 4 months to more than 18 months.

They found no significant differences in the occurrence of heart attack, stroke, hospitalization for heart failure, or any cardiac event. However, they found significant differences in the occurrence of four medication side effects.

Compared with those taking ARBs, people taking ACE inhibitors were:

· 3.3 times more likely to develop fluid accumulation and swelling of the deeper layers of the skin and mucous membranes (angioedema)

· 32% more likely to develop a cough (which may be dry, persistent, and bothersome)

· 32% more likely to develop sudden inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

· 18% more likely to develop bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract