Preparing labs for diabetic testing levels after COVID-19

For a printable version of the April CE Story and test go HERE or to take test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe the impact of COVID-19 on people with diabetes, as well as the disproportional impact on diabetic/pre-diabetic people of color and low socioeconomic populations

2. Describe the impact of lack of routine testing on diabetes management and prevention

3. Describe the challenges laboratories will face post-pandemic

4. Recall what laboratories can do to prepare for life after COVID-19

There is plenty of evidence that individuals with diabetes are at an increased risk of COVID-19. A retrospective observational study of 1,122 COVID-19 adult patients in 88 U.S. hospitals found that patients with diabetes and/or uncontrolled hyperglycemia had higher mortality rates and longer hospital stays than patients without these conditions.1A report from New Orleans claims that 97 percent of people killed by COVID-19 in Louisiana state had a pre-existing condition, and nearly 40 percent of those who died had diabetes.2

The coronavirus pandemic has placed an additional mental and physical burden on people with underlying health conditions, like diabetes. The pandemic has moved routine doctor visits to telemedicine and made outings to pick up medicine or get blood drawn yet another risk for exposure.3

Due to this, routine lab testing volumes have plummeted by approximately 60 percent as patients put off care,4 while COVID-19 has increased lab testing demands by nearly 25 percent.5 This trend continues in smaller regional and communal laboratories where the volume of routine laboratory testing has declined dramatically due to the closure of many doctor’ s offices, medical clinics, surgical centers, and other healthcare facilities.6

The impact of COVID-19 on people with diabetes

The pandemic has forced millions of people worldwide indoors and into isolation or quarantine, which affects both our physical and mental health.7

People with diabetes are more vulnerable and have a high risk of becoming seriously ill when infected with SARS-CoV-2. This can provoke anxiety and is compounded by realistic worries about the availability of diabetes medicines and technologies.8 Stress and anxiety are known to make controlling diabetes more difficult, as they throw off the much-needed daily routines, the release of stress hormones that can increase blood pressure and heart rate, and may cause blood sugar to rise.9 In addition, quarantining makes it challenging to perform daily physical activity, which is a critical focus for blood glucose management and overall health in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes.10

Not being able to get HbA1c levels tested has an adverse impact on patients with diabetes, where regular HbA1c testing is needed to control glucose levels and prevent diabetes complications. In addition, well-controlled glucose levels may prevent severe cases of COVID-19.11

The extra burden on people of color and low-socioeconomic populations

According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), African American adults are 60 percent more likely than non-Hispanic white adults to have been diagnosed with diabetes. In addition, minority populations suffer the consequences: in 2016, non-Hispanic African Americans were 3.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with end-stage renal disease as a consequence of diabetes, as compared to non-Hispanic whites; non-Hispanic African Americans were 2.3 times more likely to be hospitalized for lower limb amputations, as compared to non-Hispanic whites; and in 2017, African Americans were twice as likely as non-Hispanic whites to die from diabetes.12

People of color, particularly African Americans, are experiencing more serious illness and death due to COVID-19 than white people. This is regardless of socioeconomic status. There are many reasons for this, including systemic racism, inconsistent access to healthcare, working in essential fields, living in crowded housing conditions, and existing chronic conditions, such as diabetes.14

There is also anecdotal data to suggest that people from vulnerable populations who have COVID-19 symptoms may not be referred for testing as frequently as their white counterparts. African American and Hispanic people are more likely to experience longer wait times and understaffed testing centers. As in many cities around the country, testing sites in and near predominantly African American and Hispanic neighborhoods are likely to serve far more patients than those near predominantly white areas.15 This lack of testing can lead to further spread of infection and death – to which people with diabetes are even more susceptible.

The impact of lack of routine testing on diabetes management and prevention

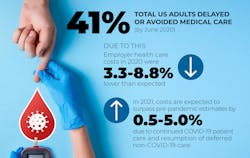

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 41 percent of U.S. adults had delayed or avoided medical care, including urgent or emergency care (12 percent) and routine care (32 percent) by the end of June 2020.16 Avoidance of urgent or emergency care was more prevalent among unpaid caregivers for adults, persons with underlying medical conditions, African American adults, Hispanic adults, young adults, and persons with disabilities.

A delay in needed medical care likely increases morbidity and mortality associated in both acute and chronic health conditions, including prediabetic patients and those with type 2 diabetes. These individuals will benefit from HbA1c testing crucial to the assessment, diagnosis and management of diabetes.17 Poor diabetes control has been proven to negatively affect prognosis and promote the risk of infection.18 Lack of testing for diabetes is also detrimental for COVID-19 outcomes for patients who have diabetes. Screening of asymptomatic patients to detect prediabetes and initiate lifestyle changes has the added benefit of reducing the risk of adverse events if a person contracts COVID-19.19

Having untreated or unmonitored diabetes can pose a serious health risk, and unfortunately, one in five adults don’t even know they have diabetes.20 The consequences of delaying treatment in type 2 diabetes can impact long-term outcomes. A study evaluated a cohort of 600,000 hypothetical patients with type 2 diabetes, based on real-world data, found that mean HbA1c at one year was 6.8 percent for patients undergoing treatment intensification (No Delay group), compared with 8.2 percent for those where treatment was delayed (Delay group). The risk for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) – myocardial infarction, stroke, and death from coronary heart disease – was lower among patients in the group who received treatment without delay. Patients in the No Delay group also had a lower five-year incidence of other complications compared to those in the Delay group, with the greatest difference observed for myocardial infarction, followed by heart failure and stroke.21

We know from literature that the first year after diagnosis is crucial for patients with type 2 diabetes, and new research shows that better control during that first year can reduce the future risk for complications, including kidney disease, eye disease, stroke, heart failure, and poor circulation to the limbs,22 making it even more important to get tested regularly and early.

Pre-pandemic challenges compound the COVID-19-related delays in testing. A study found that the median delay in diagnosis from onset of diabetes mellitus was 2.4 years, and nearly 7 percent of incident cases remained undiagnosed for at least 7.5 years after onset of the disease.23 When left unmanaged, diabetes, we know, can trigger a cascade of symptoms, ranging from mood changes to organ damage.24

Post pandemic challenges for laboratories

The introduction of vaccines is a welcome relief. Still, many industry players suggest it will not impact SARS-CoV-2 testing volumes in the near term, and the demand for COVID-19-related testing will continue through 2021 and potentially into 2022.25 This means that the pressure on healthcare utilization will continue. New challenges of operating in a COVID-19 environment limit hospital efficiency and capacity, perhaps contributing further to a future backlog. Many hospitals do not believe they will be able to return to historical procedural throughput levels, even if demand increased to previous levels or higher.26

It was estimated that employer healthcare costs in 2020 were 3.3-8.8 percent lower than originally expected due to the pandemic, as system capacity shifts and a fear of contracting the virus in medical settings continued to depress volumes. However, in 2021, costs are expected to rise by 0.5-5.0 percent above pre-pandemic projections, due to continued care for COVID-19 patients and delivery of previously deferred non-COVID-19 care.27 Doctors predict a surge of new cancer cases post-pandemic due to delay in screenings forced by the pandemic;28 this will posit true for diabetes patients and others who have chronic conditions.

As people get tested, diagnosed, and treated, a backlog in both the laboratories and doctor’s offices is expected. A case study that looked at a backlog of patients waiting for surgery following the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom found that even if surgical capacity is doubled after a month of resuming normal service, it will still take more than six months to clear the backlog. This case study shows that every healthcare system around the world is going to have to make difficult decisions post-pandemic for balancing workforce and capital resources against the needs of the patients.29

Three ways labs can labs be strong enough

Nearly 216 million COVID-19 tests have been performed in the United States since the beginning of the pandemic.30 The rapid influx of tests has meant many labs are running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with the increased demand often leading to employee burnout.31 This trend is set to continue in 2021 and beyond, due to COVID-19 as well as routine testing.

Laboratories are on the frontline of protecting everyone’s health – during and after the pandemic. So, how can labs prepare for what’s coming? Here are three recommendations:

- Change our care model. COVID-19 is forcing and will continue to force caregivers to look at new models of care, especially for chronic conditions. With an unprecedented and rapid transition to telehealth services across the country, many healthcare organizations have had to change how they approach prediabetes care. For Vidant Health in Greenville, NC, that has meant quickly shifting patients from an in-person National Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) lifestyle-change program to a new virtual format – also known as distance learning, which is offered through the internet and telephonic conference – while adapting classes to meet changing priorities.32 However, this new format does not change the need for laboratory testing. This is why laboratories must adhere to the CDC Laboratory Safety Guidelines to create an environment where people with diabetes and other high-risk conditions are comfortable getting tested – not putting off testing.

- Prioritize underserved communities. The impact of diabetes and COVID-19 is even more dire for African American, indigenous and people of color.33 While vaccination campaigns begin globally, continued outreach is one of the best ways to educate at-risk populations. Laboratories can help their healthcare organizations leverage predictive and prescriptive analytics across their population to identify those with hidden and rising risk for diabetes and/or pre-diabetes for outreach. By assessing risk progression in the diabetes population, it is possible to get ahead of issues, before they become critical and costlier in the future.34

- Get automated. Get ready. As the pandemic rages and testing volumes increase, laboratories have an opportunity to deliver high-quality results more cost-effectively and efficiently with automation, which can help to address staff shortages, while enabling resources to focus on high value, clinical tasks. There is strong evidence that an efficient total lab automation model can successfully lower laboratory diagnostics costs, while decreasing congestion in laboratories and improving efficiency35 – which is exactly what labs of all sizes will need after the pandemic to deal with the increase in testing volumes. In a laboratory, TAT is queen, and instrument downtime is the villain. Laboratories need to dust off the instruments and the backup instruments that may not have been in use during the pandemic, and ensure that they are in mint condition – with completed validation and quality control.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is forcing, and will continue to force, caregivers to look at new models of care, especially for chronic conditions, such as diabetes. Early on, healthcare utilization dropped substantially, but telemedicine use increased. In more recent months, in-person care has mostly rebounded; although, that trend could now reverse as the pandemic worsens across the country.36 With this in mind, laboratories have an opportunity to overcome testing volume challenges and help people with diabetes by streamlining workflow, ensuring impactful outreach by identifying populations at risk and enabling a safe testing environment to sustain employees’ and communities’ wellness.

References:

- Bode B; Garrett V; Messler J; McFarland R; Crowe, J; Booth R; Klonoff, DC. Glycemic characteristics and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the United States. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020; 14(4), 813–821. doi: 10.1177/1932296820924469.

- Brooks B. Why is New Orleans’ coronavirus death rate twice New York’s? Obesity is a factor. Reuters. April 2, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-new-orleans-idUSKBN21K1B0. Accessed: January 28, 2021.

- John A. Coronavirus offers new challenges to people trying to manage diabetes and kidney disease. May 11, 2020. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2020-05-11/underlying-health-conditions-diabetes-coronavirus-challenges. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- New XIFIN data reveals routine lab volume down approximately 60% but Coronavirus testing adds back nearly 20%. XIFIN 2021. https://www.xifin.com/news/press-releases/2020/new-xifin-data-reveals-routine-lab-volume-down-approximately-60-coronavirus. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Silva B. The impact of COVID-19 on molecular diagnostics. Medical Laboratory Observer. Oct 22, 2020. https://www.mlo-online.com/molecular/mdx/article/21158949/the-impact-of-covid19-on-molecular-diagnostics. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- Bonislawski A. Lab test volumes plummet as patients put off care due to COVID-19. 360 Dx. April 2, 2020. https://www.360dx.com/clinical-lab-management/lab-test-volumes-plummet-patients-put-care-due-covid-19. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Diabetes, A., 2021. Managing diabetes in the time of the coronavirus. Diabeteswhatsnext.com. https://www.diabeteswhatsnext.com/global/en/support/managing-diabetes-in-the-time-of-the-coronavirus.html. Accessed 28 January 28, 2021.

- Understanding the mental-health impact of COVID-19: Interview with an expert. Diabeteswhatsnext.com. https://www.diabeteswhatsnext.com/global/en/support/understanding-the-mental-health-impact-of-covid-19.html. January 28, 2021.

- Diabetes: stress & depression. Cleveland Clinic. 2021. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/14891-diabetes-stress--depression#:~:text=Stresspercent20canpercent20makepercent20itpercent20more,causepercent20bloodpercent20sugarpercent20topercent20rise. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Colberg S, Sigal R, Yardley J, Riddell M, Dunstan D, Paddy C, Dempsey P, Edward S, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39 (11) 2065-2079; doi: 10.2337/dc16-1728.

- Lim S., Bae JH, Kwon HS, et al. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021; 17, 11–30. doi.org/10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4.

- Diabetes and African Americans.The Office of Minority Health. 2021. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Marshall MC. Diabetes in African Americans. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:734-740. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.028274.

- Golden S. Coronavirus in African Americans and other people of color. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid19-racial-disparities. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Kim S, Vann M, Bronner L, Manthey G. Which cities have the biggest racial gaps in COVID-19 testing access?. FiveThirtyEight & ABC News. July 22, 2020. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/white-neighborhoods-have-more-access-to-covid-19-testing-sites/. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KE, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1250–1257. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4.

- Lau CS, Aw TC. HbA1c in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus: an update. OAT. 2019. doi: 10.15761/DU.1000137.

- Kosinski C, Zanchi A, Wojtusciszyn A. Diabetes and COVID-19 infection. Rev Med Suisse. 2020;16:939-43.

- Wagner M, Lohmann T. Hyperglycemia associated with hospitalization for severe COVID-19 infection. Medical Laboratory Observer. October 22, 2020. https://www.mlo-online.com/continuing-education/article/21158867/hyperglycemia-associated-with-hospitalization-for-severe-covid19-infection. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Eagle L., 2021. The importance of diabetes screening. Midwest Express Clinic. https://midwestexpressclinic.com/diabetes-screening/. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Folse HJ, Mukherjee J, Sheehan JJ, Ward AJ, Pelkey RL, Dinh TA, Qin L, Kim J. Delays in treatment intensification with oral antidiabetic drugs and risk of microvascular and macrovascular events in patients with poor glycaemic control: An individual patient simulation study, Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017; 19: 1006-1013. doi: 10.1111/dom.12913.

- Wood M. Legacy effects and the importance of early blood sugar control for diabetes. UC Chicago Medicine. August 22, 2018. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/research-and-discoveries-articles/legacy-effects-and-the-importance-of-early-blood-sugar-control-for-diabetes. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Samuels T, Cohen D, Brancati F, et al. Delayed diagnosis of incident type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the ARIC study. Am J Manag Care. 12. 717-24.

- 10 Signs of uncontrolled diabetes. Medicalnewstoday.com. 2021. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317465#Frequent-infections. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Bonislawski A. How will labs use expanded molecular testing capacities post-COVID-19? 360 Dx. December 20, 2020. https://www.360dx.com/clinical-lab-management/how-will-labs-use-expanded-molecular-testing-capacities-post-covid-19. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Berlin G, Bueno D, Gibler K, Schulz J. COVID-19 has caused the deferral of millions of elective procedures, resulting in a potential backlog of case volume. McKinsey & Company. October 2, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/cutting-through-the-covid-19-surgical-backlog. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Commins J. Coronavirus backlog could fuel higher employer healthcare costs in 2021. HealthLeaders. September 29, 2020. https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/finance/coronavirus-backlog-could-fuel-higher-employer-healthcare-costs-2021. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Cohan A. Post-pandemic surge in cancer diagnoses expected due to delayed screening, doctors say. Boston Herald. May 8, 2020. https://www.bostonherald.com/2020/05/08/post-pandemic-surge-in-cancer-diagnoses-expected-due-to-delayed-screening-doctors-say/. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Martin G, Clarke J, Markar S, Carter A. How should hospitals manage the backlog of patients awaiting surgery following the COVID-19 pandemic? A demand modelling simulation case study for carotid endarterectomy. medRxiv preprint. May 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.29.20085183doi.

- Johnson M. HHS’ Adm. Brett Giroir expounds on national COVID testing strategy at AACC. Modern Healthcare. December 16, 2020. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/safety-quality/hhs-adm-brett-giroir-expounds-national-covid-testing-strategy-aacc Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Improve your COVID-19 testing workflow and reduce the demand on employees. Clinical Lab Manager. December 1, 2020. https://www.clinicallabmanager.com/product-news/improve-your-covid-19-testing-workflow-and-reduce-the-demand-on-employees-24493. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Berg S. How to successfully offer diabetes prevention at a distance. AMA. August 25, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/diabetes/how-successfully-offer-diabetes-prevention-distance. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Statistics About Diabetes. ADA. 2021. https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/statistics-about-diabetes. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Harrison E. Diabetes & COVID-19: addressing health disparities through educational outreach. hms. https://discover.hms.com/hms-blog/diabetes-covid-19-addressing-health-disparities-through-educational-outreach. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- Lippi G, Da Rin G. Advantages and limitations of total laboratory automation: a personal overview. Clin Chem Lab Med. (CCLM), 57(6), 802-811. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1323.

- Cox C, Amin K. How have health spending and utilization changed during the coronavirus pandemic? Peterson-KFF, Health System Tracker. December 1, 2020. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-have-healthcare-utilization-and-spending-changed-so-far-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ Accessed January 28, 2021.

About the Author

Shamiram Feinglass MD, MPH

is the Vice President, Global Government and Medical Affairs at Beckman Coulter. In this position, she leads Global Medical, Government, Reimbursement, and Clinical Affairs for Life Sciences and Diagnostics and drives talent diversity in every environment in which she works or leads. Feinglass was formerly the Vice President for Global Medical and Regulatory Affairs at Zimmer, Inc.