Earning CEUs:

Respiratory tract infections (RTI) or infections in the respiratory tract are divided into upper respiratory tract infections (URI/URTI) and lower respiratory tract infections (LRI/LRTI). Though some disagreement exists regarding the exact boundary between the upper and lower respiratory tracts, URTIs occur in the respiratory tract above the lungs including throat (pharyngitis), nasopharynx (nasopharyngitis), sinus (sinusitis), larynx (laryngitis), epiglottis (epiglottitis) or trachea (trachealis). LRTIs affect the lungs and tend to be more serious than URTIs.

Respiratory tract infections can be caused by viruses or bacteria. Most of the time the infections caused by viruses do not require any treatment and resolve on their own; however, bacterial infections require appropriate antibiotic therapy. Hence, early detection of the causative organism is essential for proper patient management.

URTI—mostly viral in nature

UTRIs are the most common reasons for patients to consult a healthcare professional in the outpatient setting.1 URTIs can be mild, self-limited infections like the common cold, or can escalate to a life-threatening illness such as epiglottitis.

UTRIs are caused by viruses in approximately 90 to 98 percent of cases.2 Some of the viruses that cause UTRIs are also capable of causing LRTIs. The different viruses and the RTIs they can cause are discussed below.

Common cold and rhinovirus

Around 50 percent of the time, a common cold is caused by rhinoviruses that exist as three genotypes—A, B, and C. The common cold is the most frequently occurring URTI. Each year in the United States there are millions of cases of the common cold. Colds are the main reason that children miss school and adults miss work. Adults have an average of two to three colds per year.1 A preschool-aged child has an average of six to 10 episodes per year, and 10 to 15 percent of school-aged children have at least 12 infections per year.3

The common cold is self-limited and does not cause serious health issues. Symptoms of common cold include: sore throat, runny nose, coughing, sneezing, headache, and body ache.1

Most individuals recover within seven to 10 days. Individuals with weakened immune systems, asthma, or other respiratory conditions may develop serious complications such as bronchitis or pneumonia. Other types of viruses that may cause the common cold are: coronaviruses (10 to 15 percent); influenza viruses (five to 15 percent); respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV, ~10 percent); parainfluenza viruses (PIV, ~ five percent); enteroviruses (< five percent); and human metapneumovirus (hMPV).4

Medicine cannot cure the common cold. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS), analgesics, antihistamines, cough medicines, and decongestants are commonly used. Tylenol may be given to children. Adults can take Tylenol, aspirin, or Naproxen over-the-counter (OTC) to get relief from head and body aches.5

Influenza-like illness (ILI) and influenza virus

The next common URTI with symptoms similar to the common cold is the flu. Influenza (flu) is a contagious respiratory illness commonly caused by influenza viruses A or B—and rarely by type C.

Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on their two surface proteins: the hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N). There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes (H1 through H18), and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes (N1 through N11). Currently influenza A (H1N1) and influenza A (H3N2) subtypes are found in infected individuals. Influenza B viruses are not divided into subtypes, but various strains/lineages are found. Vaccines are available for influenza virus A and B.

The flu can cause mild to severe illness. Serious outcomes of flu infection can result in hospitalization or death. Some people, such as the elderly, young children, people with certain chronic health conditions (asthma, diabetes, or heart disease), and pregnant women are at high risk of serious flu complications. Even though the impact of the flu varies based on the virulence of the circulating flu virus and the effectiveness of flu vaccines of that season, it places a substantial burden on the health of people in the U.S. each year. Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that influenza causes between 9.2 and 35.6 million illnesses, between 140,000 and 710,000 hospitalizations, and between 12,000 and 56,000 deaths annually since 2010.6

Symptoms of flu include: fever or feeling feverish/chills, cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, muscle or body ache, headache, fatigue, and vomiting and diarrhea,7 which is common in young children.

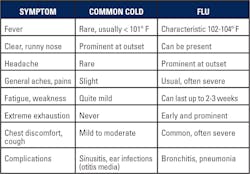

Often the common cold and the flu are confused. Table 1 differentiates between the two. The incidence of flu shows seasonality—it tends to start in October, reach a peak between December and February, and declines around May.8

Treatment for flu includes common antiviral drugs like oseltamivir (available as a generic version or under the trade name Tamiflu), zanamivir (trade name Relenza), and peramivir (trade name Rapivab). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, analgesics, antihistamines, cough medicines, and decongestants are also commonly used.9

Infections by human adenovirus

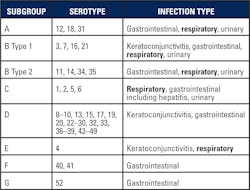

Human adenovirus (HAdV) is another virus that causes URTI-influenza like infection. Some HAdV serotypes cause conjunctivitis, gastrointestinal, and urinary infections, while some can cause Acute Respiratory Disease (ARD) which can be fatal. Table 2 illustrates the subgroups and serotypes of adenovirus and the infections they are associated with.

During the period of October 2013 to July 2014, Oregon state health authorities identified 198 persons with respiratory symptoms and an HAdV-positive respiratory tract specimen. Among the 136 (69 percent) hospitalized persons, 31 percent were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 18 percent required mechanical ventilation; five patients died.10

Some additional viruses include HAdV-B14, which has been associated with outbreaks of acute respiratory illness among U.S. military recruits and the general public since 2007. It is often termed as killer cold.11 HAdV-E4 was identified in adults with ARD in the northeastern U.S. during 2011–2015,12,14 and HAdV-B7, which can cause severe respiratory disease, is reemerging in Asia.

Treatment

Most infections by adenovirus are cleared by the immune system and do not require any medication. However in immunocompromised patients, drugs such as cidofovir, ribavirin, ganciclovir, and vidarabine have been used.13

Viruses causing both URTI and LTRI

There are many viruses that are capable of causing infections in both the upper and lower respiratory tract. The following are a few examples of such viruses:

Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is one of the most common viruses to infect children worldwide and is increasingly being recognized as an important pathogen in adults, especially the elderly. It causes mild URIs but severe LRIs.15 RSV has been implicated in severe acute respiratory illness (SARI). RSV consists of two subtypes—A and B. Subtype A is more virulent and predominate during outbreaks. Subtype B is generally asymptomatic.15 Medication used in severe high-risk cases include the antiviral drug ribavirin.16

Human Parainfluenza Virus (HPIV) can cause both upper and lower respiratory infections. It causes infections in infants and young children. Common symptoms are fever, runny nose, and cough.17

HPIV are classified as types 1, 2, 3, and 4. They cause disease of different severity. Type 4 has antigenic cross-reactivity with the mumps virus and very rarely causes respiratory infection that requires medical attention. Types 1 and 2 tend to cause epidemics in the fall, with each serotype occurring in alternate years. Type 3 is endemic and infects most children < 1 year; incidence is increased in the spring. Parainfluenza viruses can cause repeated infections, but reinfection generally causes milder illness. The most common illness in children is an URI with no or low-grade fever.17 Medication used in severe high-risk cases include the antiviral drug ribavirin.18,19

Human coronavirus (HCoV) cause URTI which can lead to LTRI. There are four common types: 229E (alpha coronavirus), NL63 (alpha coronavirus), OC43 (beta coronavirus), and HKU1 (beta coronavirus). NL63 has been associated with croup (laryngotracheobronchitis) 20 while HKU1 has been associated with febrile convulsion.21 OC43 is associated with necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroenteritis22-24 with typical URTI symptoms such as runny nose, cough, sore throat, and sometimes, fever.22 229E is also associated with URTI symptoms like common cold in immunocompetent patients and LTRI symptoms like pneumonia in immunocompromised patients.

Clinically, it is difficult to differentiate common cold by coronavirus from that by rhinovirus. There also exists rarer, more dangerous types such as MERS-CoV, which causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and SARS-CoV which can cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).25,26 Coronavirus infections are treated like a cold.27

Human metapneumo virus (HMPV) can cause upper and lower respiratory tract infections. HMPV is commonly found in the pediatric population, with high susceptibility rates in children less than two years. HMPV infection in adults normally shows mild flu-like symptoms. However, in some adult cases (especially elderly adults), severe complications such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can occur. HMPV infections have also been reported in several immunocompromised patients, such as lung transplant recipients, patients with hematological malignancies, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. HMPV exists as two genotypes: A and B.28 Medication used in severe high-risk cases include the antiviral drug ribavirin.29

Human enterovirus (HEV) are ubiquitous in nature. They can cause respiratory, gastrointestinal, and diseases of the central nervous system. The respiratory enteroviruses usually cause no symptom or mild symptoms. At times they can cause severe infection. HEV are found to have 4 genotypes: A, B, C, and D.

In 2014, an uncommon form of enterovirus, called EV-D68, was found circulating in Missouri and Illinois. Unlike the majority of enteroviruses that cause disease—mild upper respiratory illness, rash illness with fever, or neurologic illness (such as aseptic meningitis and encephalitis)—EV-D68 has been associated almost exclusively with respiratory disease, which can range from mild to severe, requiring hospitalization in an intensive care unit. Symptoms have included fever, difficulty breathing, and wheezing or asthma exacerbation.30 There is no medication for enterovirus. OTC medications like aspirin or Tylenol are given to relieve the symptoms.30

Human boca virus (HBoV) has been implicated in both upper and lower respiratory infections. The common clinical diagnoses associated with respiratory HBoV infection include URTIs, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, bronchitis, and asthma exacerbation.31 There is no medication for bocavirus. Supportive therapy is the mainstay of treatment.31 Often patients show concomitant presence of different types of viruses.

Upper and lower RTIs caused by bacteria

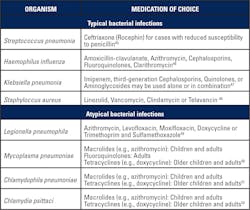

The human upper respiratory tract harbors several commensal bacteria which can occasionally turn pathogenic.32 Table 3 lists the bacteria, infection site, the URTIs they cause, and medications of choice.33 Table 4 lists the bacteria known to cause LRTIs (ie: pneumonia), both typical and atypical, as well as medications of choice.

Diagnostic methods for RTI

Viral infections often resolve on their own and unfortunately, antibiotics have no effect. Clinical manifestation is often not specific enough. Hence, proper diagnosis to determine the causative organism is very important for proper patient management. The various diagnostic tests, along with their pros and cons are listed, below.

Virus tests

- Viral culture: considered the gold standard but difficult to grow and is time consuming.

- Rapid antigen: often have low sensitivity and/or specificity.

- Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA): provides detection of multiple viruses with high specificity. Sensitivity suboptimal for some viruses and requires expertise.

- Molecular method: direct identification of viral RNA or DNA by PCR, Multiplex PCR or Real-Time PCR. Very sensitive and specific. More expensive compared to other methods.

Bacteria tests

- Gram staining: easy and rapid; however not specific.

- Bacterial culture and drug sensitivity: highly specific, sensitivity varies.

- Rapid antigen: often have low sensitivity and/or specificity.

- DFA: provides multiple bacteria detection with high specificity; suboptimal for some bacteria and requires expertise.

- Molecular method: direct identification of viral RNA or DNA by PCR, Multiplex PCR or Real-Time PCR; very sensitive, specific; more expensive compared to other methods.

Commercial RTI tests that identify multiple viruses and/or bacteria using multiplex PCR technology offer convenient method of detection and are highly sensitive and specific.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Common Colds: Protect Yourself and Others. Feb. 2018.

- Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guidelines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012:1-41. doi:10.1093/cid/cir1043.

- May Loo, MD Chapter 60. Upper Respiratory Tract Infection. Integrative Medicine for Children 2009, Pages 450–455.

- Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003; 361(9351):51-59.

- https://www.webmd.com/cold-and-flu/understanding-common-cold-treatment#1

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/burden.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/keyfacts.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season.htm

- https://www.webmd.com/cold-and-flu/flu-treatment#1

- Ghebremedhin. Human adenovirus: Viral pathogen with increasing importance. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp). 2014 Mar; 4(1): 26–33.

- Scott M, Chommanard C, Lu X, Appelgate D, Grenz L, Schneider E, et al. Human Adenovirus Associated with Severe Respiratory Infection, Oregon, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(6):1044-1051.

- https://www.cdc.gov/adenovirus/outbreaks.html

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/211738-treatment

- Kajon AE, Lamson DM, Bair CR, Lu X, Landry ML, Menegus M, et al. Adenovirus Type 4 Respiratory Infections among Civilian Adults, Northeastern United States, 2011–2015. Emerg Infe Schweitzer JW, Justice NA.

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV) [Updated 2017 Oct 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459215/ct Dis. 2018;24(2):201-209. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2402.171407

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/971488-medication

- https://www.cdc.gov/parainfluenza/index.html

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/224708-treatment

- https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/respiratory-viruses/parainfluenza-virus-infections

- van der Hoek L., K. Sure, G. Ihorst, A. Stang, K. Pyrc, M. F. Jebbink, G. Petersen, J. Forster, B. Berkhout, K. Ãœberla. 2005. Croup is associated with the novel coronavirus NL63. PLoS Med. 2:e240. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lau S. K. P., P. C. Y. Woo, C. C. Y. Yip, H. Tse, H. W. Tsoi, V. C. C. Cheng, P. Lee B. S. F., Tang C. H. Y., Cheung R. A. Lee, L. Y. So, Y. L. Lau, K. H. Chan, K. Y. Yuen. 2006. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2063-2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gerna G., N. Passarani, M. Battaglia, E. G. Rondanelli. 1985. Human enteric coronaviruses: antigenic relatedness to human coronavirus OC43 and possible etiologic role in viral gastroenteritis. J. Infect. Dis. 151:796-803. [PubMed]

- https://www.cdc.gov/non-polio-enterovirus/about/prevention-treatment.html

- Resta S., J. P. Luby, C. R. Rosenfeld, J. D. Siegel. 1985. Isolation and propagation of a human enteric coronavirus. Science 229:978-981. [PubMed]

- Jean A1, Quach C, Yung A, Semret M. Severity and outcome associated with human coronavirus OC43 infections among children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 Apr; 32(4):325-9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182812787.

- https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/mers-and-sars

- https://www.webmd.com/lung/coronavirus#1

- Swagatika Panda, et. al. Human metapneumovirus: review of an important respiratory pathogen. International Journal of Infectious Diseases Volume 25, August 2014, Pages 45-52.

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/237691-treatment

- http://www.dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/diseases-and-conditions/diseases-a-z-list/enterovirus

- Schildgen O., et al. Human bocavirus: passenger or pathogen in acute respiratory tract infections? Clin Microbiol Rev 21, 291–304 (2008).

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/302460-overview

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8142/

- https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/gram-positive-cocci/streptococcal-infections

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/215100-treatment

- https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/treatment.htm

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1165557-medication

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1054547-medication

- https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/cpneumoniae/hcp/treatment.html

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1941994-medication

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/218271-treatment

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/222320-treatment

- https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/treatment.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5414a1.htm

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/225811-medication

- https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/bacterial-infections-gram-negative-bacteria/haemophilus-influenzae-infections

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/219907-treatment

- https://www.hopkinsguides.com/hopkins/view/Johns_Hopkins_ABX_Guide/540518/all/Staphylococcus_aureus#3.5

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/965492-treatment

- https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/mycoplasma/hcp/antibiotic-treatment-resistance.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/cpneumoniae/hcp/treatment.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlamydia_psittaci#Treatment