Testing for sexually transmitted infections

To take the test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to:

1. List the main sexually transmitted pathogens and the diseases they cause.

2. Discuss STIs that can result in a risk of cancer.

3. List and describe the test methodologies used for diagnosis of STIs and the benefits of each.

4. Describe the type of settings that STI testing is used in.

Infections transmitted through sexual contact, including vaginal, anal, and oral sex are called sexually transmitted infections (STI)s. There are more than 30 different bacteria, viruses, and parasites that can cause STIs.1 And some infections can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding.1 STIs are a global health problem, including in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) 2022 STI Surveillance Report, more than 2.5 million cases of Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis were reported in the United States, making STI a great public health concern.9

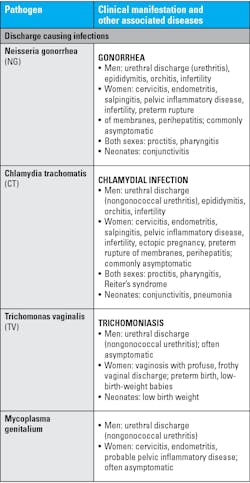

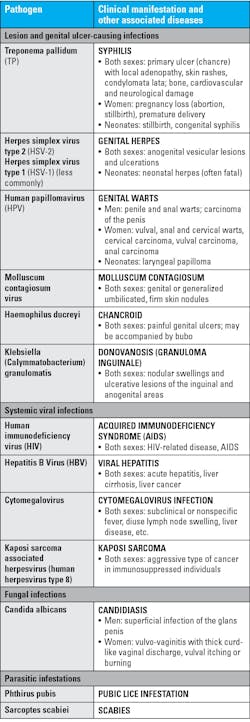

Most common STIs and the diseases they cause

The most common STI-causing pathogens and the diseases they cause are provided in Table 1 below: 2

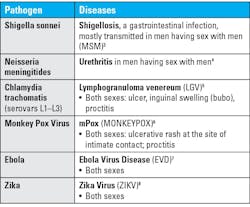

Emerging STIs

Some emerging outbreaks acquired by sexual contact and their diseases are listed in Table 2 below:

Consequences of STIs10

STIs affect fertility

STIs, if left untreated, cause damage to the reproductive organs. STIs like Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Trichomatis cause infection of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries in females, resulting in inflammation, i.e., swelling and scarring of these organs leading to a condition called Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). According to a CDC estimate, more than 1 million women are annually diagnosed with PID in the United States.11 The inflammation and scarring from these infections can be permanent and result in ectopic pregnancy or infertility later in life.

STIs increase the risk of cancer

STIs have been shown to increase the risk of developing certain cancers. The STI infections that can cause cancer are:

Human papillomavirus (HPV) – HPV is a group of over 200 viral genotypes. They can be transmitted through vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Based on their risk of causing cancer, they are classified as high risk or oncogenic HPV and low risk or non-oncogenic type.12 High-risk HPVs can cause several types of cancer — anal, cervical, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar. 12 There are 12 high-risk HPV types: HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59. HPV 16 and HPV 18 are responsible for most HPV-related cancers.12

Low-risk HPV types rarely cause cancer, although a few low-risk HPV types can cause warts on or around the genitals, anus, mouth, or throat. When warts form in the larynx or respiratory tract, it leads to a condition called respiratory papillomatosis, which can cause breathing problems.12

HPV infections are often cleared by the host’s innate defense mechanism. It is believed, up to 90% of high-grade, pre-cancerous lesions in young women regress without treatment in two years. Only 5% of HPV infections progress to CIN 2 or CIN 3 within three years. Of those that progress, 80% CIN 3 lesions regress, and approximately 20% progress to invasive carcinoma within five years. Of this 20%, only 40% progress to invasive carcinoma within 30 years. HPV infection can lead to cervical cancer only if the high-risk HPV type(s) persist for long enough to cause abnormalities in the cervix.13

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) — HBV is transmitted through blood, semen, or another body fluid from a person infected with the virus to someone who is uninfected by sexual contact; sharing needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment; or from the gestational parent to baby during pregnancy or at birth.

For some, hepatitis B is an acute, or short-term, illness; for others, it can become a long-term, chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis B can lead to cirrhosis, liver cancer, and even death.14

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — HIV may not cause cancer directly, but over time it causes the immune system to weaken, putting people living with HIV (PLWH) at an increased risk of developing opportunistic cancers, considered as AIDS-defining cancers. The commonly observed cancers are

Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cervical cancer.15 In addition, many STIs including Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhea, HSV have been shown to increase the risk for HIV infection.

Symptoms of STIs

Some of the common symptoms of STIs are as follows: 16

- Unusual discharge from the vagina, penis, or anus

- Pain when peeing

- Lumps or skin growths around genitals or anus

- Rash

- Unusual vaginal bleeding

- Itchy genitals or anus

- Blisters, sores, or warts around genitals or anus

- Warts in the mouth or throat, but this is very rare

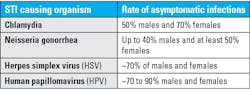

Asymptomatic STIs

Often STIs show no apparent symptoms. Asymptomatic rates10 for some of the common STIs are shown below in Table 3:

Types of tests for STIs

Testing for STIs is always high in demand and a broad array of tests are available for detection of STIs.

Tests can be broadly classified into three types:2

- Direct detection of the STI-causing microbe using the following techniques:

- Microscopy – A simple, rapid, and inexpensive test that can be performed at the doctor’s office to help physicians get a presumptive diagnosis and recommend proper treatment to manage patients. The sensitivity is dependent on the user’s skills and tends to be lower in asymptomatic patients.17, 18 The analysis needs to be performed within 10 minutes of sample collection and so unsuitable for testing in reference laboratories.19

- Culture – Some STI-causing organisms can be grown using specific media with good sensitivity and specificity. Though it may take days, it is the only reliable method to test for antimicrobial resistance. However, some STIs such as Treponema pallidum and HPV cannot be cultured and culturing Chlamydia trachomatis and HSV require specialized laboratories making it very expensive. Neisseria gonorrhea samples are very fragile and often die before they reach the laboratory for culture, making the test less sensitive. The efficiency and precision of culture has been recently increased with the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.20

- Detection of antigens – Antigen detection-based assays allow the diagnosis of current infections. Commercially available antigen-based rapid detection tests (RDTs) are easy to use and require minimal skill. Some RDTs use lateral flow immunochromatographic (ICT) assays that can also be used at the point-of-care (POC) enabling doctors to diagnose and treat patients in one visit. However, they are not as sensitive as nucleic acid–based tests and some tests may also show false positive results.20

- Detection by molecular method/nucleic acid-based test – Detection of STIs using nucleic-acid (DNA or RNA) amplification technique is now considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of many STIs. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) have a significantly lower turnaround time than culture, have a significantly higher sensitivity than all other tests, and may be used to screen asymptomatic cases. Though molecular tests need skilled personnel, many NAATs have been standardized and automated requiring minimal skills, and they can be multiplexed, allowing simultaneous detection of multiple organisms from the same sample. Some NAATs can also become POC tests for their ease of use. There are also many other nucleic acid–based tests that may or may not use amplification technique, which are also highly sensitive and specific.20

- Detection of host response or antibodies to infection – Serological tests are useful for diagnosis, monitoring therapy, or surveillance purpose.21 The serological test is considered the gold-standard for syphilis.22 Serological testing was also commonly used to determine past exposure to HSV.

- Detection of microbial metabolites – Certain tests detect microbial metabolites that alter the pH of genital secretions and biogenic amines to analyze presence of STIs.2

Tables 4a and 4b list different testing methods for a few common STIs.20

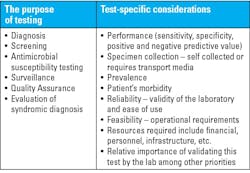

The factors that need to be kept in mind when selecting a test are shown in Table 5:2

Conclusion

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) pose far-reaching implications with respect to social, economic, and public health globally, including in the United States. In the United States, it has been reported that over 50 percent of infections are in the age group of 15 to 24.23 To prevent and control STIs, a multi-pronged approach needs to be taken that includes education, early disease diagnosis, and treatment. To monitor the STI epidemic, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has launched a 5-year STI Implementation Plan24 and intends to monitor through 2030. That said, it is the responsibility of all sexually active men and women to use all precautions when indulging in sexual activity, be proactive in testing for sexual infections, and getting treated if found infected. STI testing is available in various settings including clinical laboratories, point-of-care tests in doctor’s offices and hospitals, and home-based tests. The availability of point-of-care tests and home-based tests have made testing for STIs easier. With advancement in molecular technologies, we can hope to have more point-of-care tests that are accurate, rapid, and easy to use with reasonably low cost that can be used to diagnose and treat STIs early and curb the spread of STIs.

References

- Sexually transmitted infections (STI)s. World Health Organization. May 21, 2024. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)?.

- Unemo M, Cole M, Lewis D, Ndowa F, Van Der Pol B, Wi T, editors. Laboratory and point-of-care diagnostic testing for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Faherty EAG, Kling K, Barbian HJ, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Shigella sonnei cluster among men who have sex with men in Chicago, Illinois-July-October 2022. J Infect Dis. Published online 2024. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiae235.

- Jannic A, Mammeri H, Larcher L, et al. Orogenital transmission of Neisseria meningitidis causing acute urethritis in men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(1):175-176. doi:10.3201/eid2501.171102.

- Rawla P, Thandra KC, Limaiem F. Lymphogranuloma venereum. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Allan-Blitz LT, Klausner JD. Current evidence demonstrates that monkeypox is a sexually transmitted infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2023;50(2):63-65. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001705.

- Rogstad KE, Tunbridge A. Ebola virus as a sexually transmitted infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28(1):83-5. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000135.

- Sexual transmission of Zika Virus. CDC. August 14, 2024. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/hcp/sexual-transmission/index.html.

- Sexually transmitted infections surveillance, 2022. CDC. July 8, 2024. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/default.htm.

- Bishop C. The dangers of undiagnosed sexually transmitted infections. American Society for Microbiology. December 8, 2022. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://asm.org/Articles/2022/December/The-Dangers-of-Undiagnosed-Sexually-Transmitted-In.

- Kreisel K, Torrone E, Bernstein K, Hong J, Gorwitz R. Prevalence of pelvic inflammatory disease in sexually experienced women of reproductive age - United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(3):80-83. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6603a3.

- HPV and Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Updated October 18, 2023. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer.

- Chandra R. Relevance of persistent infection with high-risk HPV genotypes in cervical cancer progression. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2013;45(10):40, 42, 44.

- Hepatitis B Surveillance 2021. CDC. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2021surveillance/hepatitis-b.htm.

- HIV infection and cancer risk. National Cancer Institute. Updated September 14, 2017. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hiv-fact-sheet#.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). National Health Services (NHS), UK. Updated May 13, 2024. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis/.

- Meyer T, Buder S. The laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Current testing and future demands. Pathogens. 2020;9(2):91. doi:10.3390/pathogens9020091.

- Van Der Pol B. Clinical and laboratory testing for Trichomonas vaginalis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(1):7-12. doi:10.1128/JCM.02025-15.

- Kissinger P. Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:307. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1055-0.

- Caruso G, Giammanco A, Virruso R, Fasciana T. Current and future trends in the laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1038. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031038.

- Thomas DL, Quinn TC. Serologic testing for sexually transmitted diseases. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7(4):793-824.

- Papp JR, Park IU, Fakile Y, et al. CDC laboratory recommendations for syphilis testing, United States, 2024. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2024;73(1):1-32. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7301a1.

- National Overview of STIs, 2022. CDC. Updated January 30, 2024. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/overview.htm.

- HHS releases first-ever STI federal implementation plan. HHS. June 8, 2023. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/06/08/hhs-releases-first-ever-sti-federal-implementation-plan.html#.

To take the test online go HERE. For more information, visit the Continuing Education tab.

About the Author

Rajasri Chandra, MS, MBA

is a global marketing leader with expertise in managing upstream, downstream, strategic, tactical, traditional, and digital marketing in biotech, in vitro diagnostics, life sciences, and pharmaceutical industries. Raj is an orchestrator of go-to-market strategies driving complete product life cycle from ideation to commercialization.